In Part Two, we'll continue with the engine internals, going back to the rise of fuel injected engines and the efforts by carmakers – led by BMW North America – to improve the quality of US gasoline, the federal mandates for gasoline and the introduction of the Top Tier Gas designation. We'll then move onto Shell in particular, and how its work with the Ferrari Formula One team led to V-Power premium gas.

As with Part One, the facts in Part Two apply to every gasoline refiner. We'll refer to Shell products specifically because it was their Technology Center we visited and their engineers we spoke to, but the gasoline education pages for Chevron, Exxon Mobil and BP all say the same thing up until the line, "You should buy our gas because...", and the automaker research and the scientific studies take no sides.

So follow along – we're almost done.

We might as well be honest. As for whether Big Oil wants you to buy expensive gas, we can answer that right now: of course they do. Porsche wants you to buy its 918 Spyder and The Mars Company wants you to buy the biggest bag of M&Ms, so we don't consider that outrageous. None of them will force you to do it, and in the matter of gasoline, in some cases, it might make sense to.

There's a basic, federally mandated standard for gasoline, and after refining, all gas is the same – the initial, refined gasoline from Shell would be indistinguishable from what Chevron, BP and Arco refine. Gas companies are known by their additives, by how they change – with the intent of improving – the basic formulation. "V-Power" is the name of Shell's premium gasoline, and it contains the highest concentration of proprietary detergents of the three grades of gas you'll find at Shell stations. The brand name of those detergents is "Nitrogen Enriched Cleaning System," because "Shell specialty polymer compound" isn't cool at all. The same goes for Techron (Chevron) and Invigorate (BP).There's a basic, federally mandated standard for gasoline, and after refining, all gas is the same.

Additives formulated to clean car engines have been around for decades – carburetor detergents were introduced in 1954 – and they help clean up the unwanted hydrocarbon compounds that turn into "gunk." This is a simplification, but additives combine chemically with solid debris and flush it out of the system, and prevent deposit-forming compounds in gasoline from building up gunk in the first place. Shell's nitrogen-enriched product is an oil-soluble chemical additive system developed to counter carbonaceous buildup, working both to clean up deposits that already exist and, via molecules meant to adhere to the metal, inhibit the buildup of deposits.

When fuel injection began being widely adopted in the 1980s, automakers discovered that injectors were getting badly clogged because of 'dirty' gas. When steps were taken to fix the problem, the newly introduced detergents cleaned the injectors but left deposits on the intake valves. In the mid-'80s, BMW North America partnered with the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) to study how gasoline and driving styles were affecting intake deposit buildup, and in some of the tests it was found that as much as two grams of deposits had accumulated on valves in as little as 10,000 miles. Two grams after 10,000 miles sounds like nothing, but BMW NA's limit for acceptable performance was 250 milligrams after 50,000 miles of driving – there was supposed to be less than a tenth of a percent of what was actually being found in order to ensure satisfactory performance, and only after five times more driving. And this was the spec for engines in the '80s – the test vehicle was a 1985 318ti – when tolerances weren't what they are today. The final spec was set at less than 100 mg/valve average after 50,000 miles.Detergents that clean injectors can foul the intake valves, and intake deposits can then lead to more combustion chamber deposits.

Other automakers began to acknowledge the problem and that led to a consortium that petitioned refiners and the US government to increase the detergents in gasoline. What was really needed was a detergent cocktail, because different kind of deposit compositions are fought with different chemical detergents, and detergents have their own issues; as BMW discovered, detergents that clean injectors can foul the intake valves, and intake deposits can then lead to more combustion chamber deposits.

After years of automakers petitioning the Environmental Protection Agency to mandate detergent use in gasoline, the EPA did so in 1995 with an interim program. It followed that with a certification program for detergent additives that came into effect in 1997 and established a lowest common denominator for deposit control performance. That meant oil companies had to pass two standard deposit control tests, at the time called the ASTM D 5500-97 BMW intake-valve deposit test and the ASTM D 5598-95 Chrysler 2.2-liter port-fuel-injector test, in order to have their fuel certified. Every gallon of gas sold in the US has to contain the certified additives that address intake valve deposits and port fuel injector deposits.

However, there were two problems with the ruling. When it was introduced, it had already fallen behind engine technology, so carmakers felt it didn't go far enough to keep engines clean, and it also mandated a level of detergent – called the Lowest Additive Concentration (LAC) – that was below what some gas companies were using, so certain gas producers reduced the amount of detergent to the federally mandated minimum.Some fuel additives, when used at very low concentrations, can actually increase the level of gunk.

At the Technology Center, we were shown a couple of intake valves showing such buildup, and told that it only takes about 5,000 miles to start registering carbon deposits. We were surprised to find that one valve that had been run with an LAC gas exhibited more carbon buildup than a valve used in an engine run with untreated gas. Shell engineers told us that some fuel additives, when used at very low concentrations, can actually increase the level of gunk.

This led to BMW, General Motors, Honda, and Toyota creating a group called Top Tier Gas (TTG) in 2002. Gas retailers who earn the Top Tier Gas designation use more detergent than the EPA mandates, but the point of TTG is not about a particular amount of detergent, it's about maintaining the higher performance standards dictated by car companies concerning their engine tolerances and cleanliness. There are currently 23 Top Tier Gas retailers in the US and four in Canada, one of which is Shell (along with Chevron, BP and Exxon), and all grades of gas sold in every retail station of a certified producer have to meet TTG standards – a producer can't just get its premium gas certified.Gas retailers who earn the Top Tier Gas designation use more detergent than the EPA mandates.

Not being TTG certified doesn't mean a producer uses only the LAC, but TTG certification gives buyers a way to know what they're buying. And if you think TTG is just another arm of the conspiracy to get you to buy 'name brand' gas, you'll have to include the Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE) among the corrupt, since they recommend it, too.

TTG is important because it came along with the rise of direct injection engines, and DI motors have made the need for detergents even greater. First, DI engines work with higher pressures and the gas and chamber temperatures are higher. That makes the conditions more ripe for carbon deposits. Plus, the quest for more horsepower, higher fuel economy and greater emissions control means tighter tolerances and running at lean limits through more of the rev range, so any variances have larger effects. Second, in a port fuel-injected engine, fuel is sprayed into the channel behind the intake valve and gets sucked into the cylinder past the valve, with the air. This means the fuel can act as a bath, washing the intake valve with detergents as it passes into the cylinder. Direct injected engines spray fuel directly into the chamber, so the intakes don't benefit from that cleaning – even though fuel does end up on the valves because the intakes aren't yet fully closed when the fuel is sprayed into the chamber (animations of an EcoBoost engine and a DI engine from GM show how it happens). Without the injector spraying any detergents over the valves, there's little remedy for the oily residue circulating because of the PCV and EGR systems, and the bits of fuel that get stuck to that residue. For an example of how it can go wrong, Edmunds' AutoObserver had a story about an Audi RS4 that lost 40 hp in just 10,000 miles because of carbon and sludge buildup issues with Volkswagen and Audi DI engines of the time (that have since been resolved).TTG is important because it came along with the rise of direct injection engines.

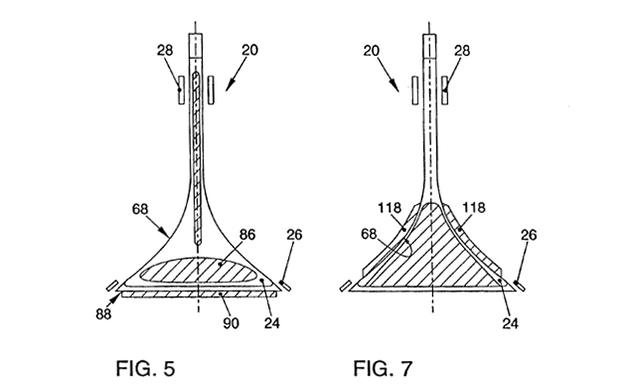

Volkswagen applied for a patent in 2002 that it was granted in 2005 for an invention to keep DI engine intake valves clean using a metallic coating that would inhibit the buildup of deposits, but so far, VW doesn't appear to have applied the technology. General Motors' Gen-V small-block was designed with a special set of baffles that serve the same purpose.

Point being: detergent additives are in gasoline for a reason and aren't made from the boiled bones of jackalopes, meant for sale at 4H fairs and rural bus stop benches. And so, we come to nitrogen-enriched V-Power.While all grades of Shell gasoline are designed to clean up existing deposits, the idea is that V-Power will do so faster because it has more cleaning agents.

Shell says it was the largest investor in R&D last year, kicking in $1.3 billion, and part of that loot gets spent at a place like this, the Shell Technology Center, 20 miles west of Houston. It's one of the largest technical centers in the Shell empire, where 2,000 fuels scientists, engineers, technicians and support employees occupy its one million square feet in 44 buildings on 200 acres searching for better fuels. They work with technical groups from upstream and downstream who are looking for synergies in the production of gasoline. Those gasoline hydrocarbons we mentioned earlier? Think of them like grapes for winemaking, and Shell engineers are the hydrocarbon connoisseurs who optimize the refining process around a specific hydrocarbon to make the best product, whether that be automotive gas or some other stock.

As per the Top Tier Gas rule that "fuel marketers use the same minimum detergency treat rate for all octane grades of gasoline sold at their stations," all Shell gasoline – regular, mid-grade and premium – contains the nitrogen-enriched cleaning system. Gasoline producers can use more detergent in a blend than is required by Top Tier, though, and that's what Shell has done with its V-Power premium; it contains the highest detergent concentration. While all grades of Shell gasoline are designed to clean up existing deposits, the idea is that V-Power will do so faster because it has more cleaning agents. The regular- and mid-grade blends have at least twice the EPA-required levels of detergent, while V-Power has five times the Lowest Additive Concentration – but all blends are TTG-certified and have passed the performance tests.

We don't know what's in V-Power, but we can tell you where it came from: Shell's work with the Ferrari Formula One team. Shell partnered with Ferrari the moment Enzo started his racing team in 1929, and it has been with the Scuderia for more than 60 years, stepping aside from 1974 to 1995 when Agip took over. Shell rejoined Ferrari at the beginning of 1996 with a proper technical partnership that aimed to create and test different fuels for the same reason that automakers get into motorsports: to prove its products in the toughest environment. It now provides the team with fluids and lubricants like gas, Helix oil, Spirax gearbox and transmission fluid, Tellus hydraulic fluid, Gadus grease and KERS coolant. V-Power emerged from that motorsports experience and went on sale in its first market, Hong Kong, in 1998. We were told that 99.1 percent of the same types of components in that race fuel are in the Shell V-Power fuel you buy at your local station.99.1 percent of the same types of components in that race fuel are in the Shell V-Power fuel you buy at your local station.

We were taken into a lab in one of the buildings where detailed analysis of fuels is done, and if someone had told us we were inside the aforementioned Argonne National Laboratory, or NASA, we'd have had a hard time disputing it. It was a room where 60 gas chromatographs break down the molecular construction of gasoline; where formulations are run through a capillary gas chromatography column – a hollow wire that is 250 micrometers thick, and when gasoline is run through it, it breaks out a fuel's heavy-, middle- and lightweight volatile components; where hot-plate tests show how fuel performs at 690 degrees, which happens to be how hot the intake surfaces can get in an F1 engine.

But they don't make race formulations in Houston – that happens at the Shell Technology Center in Hamburg, Germany (and they ship the gas in sealed containers to each race). Power, torque and friction results are tested for each blend, and there are usually 20 blends tested before one makes it to the track. Then, every F1 weekend, Shell parks its Trackside Lab at the host circuit and analyzes the bespoke fuel formulations developed in Hamburg, making sure they continue to match the chromatograph fingerprint of the fuel supplied to FIA from the first test session to the end of the race.

Shell also works with Ferrari's road car division to develop fuels and help the company's engineers understand how the variety of fuels found in markets around the world interact with high-compression engines. Before they made it to showrooms, the California, F12 and LaFerrari were tested for calibration problems and contamination of injector tips with Shell gasoline. And every Ferrari is driven off the dealer lot with a full tank of Shell V-Power.Every Ferrari is driven off the dealer lot with a full tank of Shell V-Power.

And that, friends, is a small part of the story of Shell, V-Power, gasolines, detergents, your engines and the government. This, we'll admit, was the hard part of the assignment, but we wanted to give some idea of the secret life of your car engine and gasoline, and make the case that even once you get behind all the marketing hullabaloo, all gas is not the same at all pumps.

Sign in to post

Please sign in to leave a comment.

Continue