Coskata Lighthouse Cellulosic Ethanol Plant - Click above for high-res image gallery

Coskata's newly-opened semi-commercial flex ethanol facility in Madison, Pennsylvania is as small as it can possibly be. Co-located at a Westinghouse facility that also in some fashion uses nuclear energy, the Lighthouse project, as it's called, is running 24/7 to turn wood chips into ethanol. It's also intended to show off just how far Coskata has come since emerging from stealth mode almost two years ago. Oh, and the plant can also be scaled up to fit the needs of cellulosic ethanol producers from coast to coast.

The Lighthouse plant follows the Horizon integrated processing plant that started in 2008 in Warrenville, Illinois and precedes the Flagship plant that is due for 2012 at a location somewhere in the Southeast U.S. that will be announced later. The location for the Flagship plant has been selected, but Coskata will not specify where it is exactly until it can talk more specifically about the financing arrangements involved for the 55-million-gallon-per-year plant that will use forest residue and other woody biomass. Coskata says the Flagship will be "the first commercially-viable, feedstock-flexible ethanol facility." Coskata has not taken any government money to date, but they may apply for DOE loan guarantees for the Flagship plant. Coskata will not expand the Madison Lighthouse facility. In fact, they're only located there as a guest and will leave when the contract is up. The facility is modular and will actually be dismantled and trucked to the Flagship location in the future.

What might this plant offer, both for partner GM and for the U.S.'s biofuel needs? Find out after the jump.

Photos copyright ©2009 Sebastian Blanco / Weblogs, Inc.

What is flex ethanol?

Flex ethanol is the term Coskata is using for ethanol that can be made with almost any feedstock, i.e., ethanol made using the Coskata process. As we've heard since day one, the plasma torches and microorganisms can turn everything from tires to coal to municipal waste into ethanol. Flexible inputs = flex ethanol.

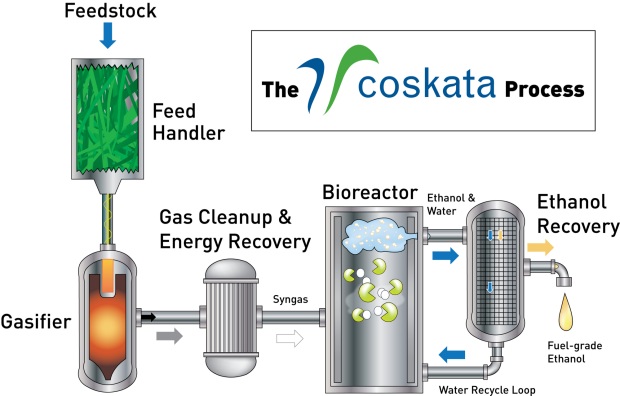

Making flex ethanol is fast, too. Coskata CEO Bill Roe said that it takes "just minutes" to go from feedstock to ethanol. The Coskata process is continuous, not a batch process, and the entire team we heard from in Madison was clear that there are no longer any technical hurdles to overcome in order to start full-scale cellulosic ethanol production using this system. As shown in the slide below, the feedstock is sent into the gasifier where the plasma torches create a gas. This gas needs to be cleaned and is then sent into the bioreactor where Coskata's proprietary microorganisms (shaped like PacMan, apparently) eat it and make ethanol. Compared to standard gasoline, Coskata's cellulosic ethanol reduces greenhouse gases by about 96 percent and uses half as much water. The microorganisms could also be tuned to make butanol or other chemicals, but the focus is on ethanol for now.

The prehistoric anaerobic microorganisms are from the family of clostridium bacteria. These "bugs" are found in nature, typically in deep-water ponds. Cosakata has managed the strains with nutrient programs and selection process to make them more efficient at producing ethanol. Coskata "did what Mother Nature would do, but on an accelerated path," Roe said. The microorganisms were discovered and developed with help from the Oklahoma Biofuels Consortium, made up of OSU, BYU and OU.

OK, what does it mean for E85 in the U.S.?

Coskata used to say that it would be able to make (not sell) ethanol for $1 a gallon. At the plant unveiling in Madison, that number was not mentioned a single time. Instead, Richard Fish from Alter NRG (home to the Westinghouse Plasma Corporation and a partner to Coskata) said that the Coskata system is able to produce ethanol at "a very competitive price" compared to the market as a whole. A "very competitive price"? How much is that? Roe explained that the exact cost depends on the feedstock going into the gasifier. Municipal waste will get you ethanol that costs much less than a dollar a gallon, virgin hardwood would cost you much more (but anyone using that particular feedstock is of questionable sanity).

In any case, Coskata doesn't see itself really competing with other renewable energy companies – "We need a lot of producers in this industry," said Coskata CMO Wes Bolsen. "I don't see anyone in the biofuel industry as a competitor" – and has its sights set on gasoline. As long as Coskata ethanol can be made cheaper than gasoline – which requires that oil costs something in the area of $65 a barrel and that producers can get biomass for $50 a dry ton – the company thinks it has a winner.

What is GM's role?

GM has invested an unspecified amount in Coskata. While the money and association certainly don't hurt Coskata's efforts to bring cellulosic ethanol to market, the biofuel company has received large investments from other groups as well (including Vinod Khosla's venture capital fund). The bigger question is what does Coskata (and Mascoma, another company The General has invested in) do for GM?

Bob Babik, GM vehicle emissions director, was on hand in Madison to share GM's fuel diversification strategy, which is absolutely nothing new. These days, though, we more often hear GM talk about plug-in and hydrogen vehicles; the longer-term, sexy technologies. Biofuels? There's no thrill in that.

But biofuels are important to GM. Very important. GM started looking for biofuel partners in 2007 and was interested in the flexible input streams that Coskata can use in their production process. Getting cellulosic ethanol to market is a good thing, Babik said, because 96 percent of all vehicles on the road today still rely on petroleum. Biofuels offer a low-cost, feasible alternative to petroleum, and can do so sooner rather than later. The vehicles are here, after all. Worldwide, GM has built over five million flex-fuel vehicles and has publicly committed to having over 50 percent of its vehicles be E85-capable by 2012.

GM does get an immediate benefit from the ethanol that Coskata is making today. "We feel beholden to GM, for all that they've done for us," Roe said, explaining why some of the ethanol produced in Pennsylvania will be shipped up to Michigan for GM's testing purposes.

What could the U.S. get from all of this?

The U.S. government has set a Renewable Fuel Standard that increases the volume of renewable fuel required to be blended into gasoline from 9 billion gallons in 2008 to 36 billion gallons by 2022. Coskata executives are dubious that the U.S. can reach this goal, especially without help from next-gen biofuel companies like Coskata.

Coskata's CMO, Wes Bolsen, said that Coskata plans on licensing the technology to other companies and he expects 4-6 commercial facilities to be spun off "fairly quick" now that the Lighthouse plant has been unveiled to the public. The feedstocks for these other plants will be determined by the company leasing the technology. Wood chips are readily available today, and construction waste and bagasse are also likely candidates. Bolsen couldn't say what he expects will be the most common feedstock for the Coskata plants of the near future, because biomass is such a local issue. Since Coskata plants could be made in all 50 states, Bolsen said there is no reason to build an ethanol pipeline in the U.S. Coskata would like to expand overseas, but it is currently "laser focused" on the U.S. market in order to meet the RFS mandate.

How can Coskata make more energy than it uses?

Argonne National Lab has found that with certain feedstocks, the Coskata process can "reach a net energy balance of 7.7" (meaning, the ethanol produced contains 7.7 times as much energy as it took to make the fuel). Because we've seen a lot of, um, interesting claims from people in the green car space regarding energy returns, we thought it makes sense to make it clear no one is claiming Coskata has invented a perpetual motion machine.

For one thing, the system requires a constant influx of biomass, and the microorganisms need to be culled and replaced every few days. The production process itself is made as efficient as possible. It takes electricity to power the plasma torches, pumps, etc., and this generates excess heat. Some of this is recaptured; more is lost. Most importantly, the ethanol is made from the carbon energy trapped in the feedstock, so the Coskata process is really just converting energy trapped inside wood, for example, into liquid fuel. There's no hocus-pocus going on here. Think of it as a BTU conversion process. We made sure Roe explained it very clearly for everyone to understand, as you can hear in our interview with him (4.6 MB, 9:30 min, download here):

The video meant to be presented here is no longer available. Sorry for the inconvenience.

Our travel and lodging for this media event was provided by the manufacturer.

Sign in to post

Please sign in to leave a comment.

Continue