What's so interesting about a plant tour? If we're honest, usually nothing. In most cases, we go on them because they're part of a larger trip – the vegetables we endure while we wait for the dessert of the press-trip drive – and we stroll narrow concrete halls avoiding forklifts and bodily injury so we can watch workers bolt large sub-assemblies together, and then finally, voilà, admire a color-wheel phalanx of [insert mass-market car here] arrayed for delivery.Our first thought on stepping onto the plant floor: "Modern Marvels, here we come."

The problem is that by the time you get to the assembly stage for most mass-production cars, you've gone past the most interesting part, because affixing sub-assemblies to one another is a bit like building a pre-fab house. It can be interesting. Once. Even at Maranello, for instance, watching a Ferrari worker attach an instrument panel to a bulkhead is all right the first time. But we could spend hours watching a woman hand-wrap the cut pieces of leather over each piece of that panel using nothing more than elbow grease and a hair dryer.

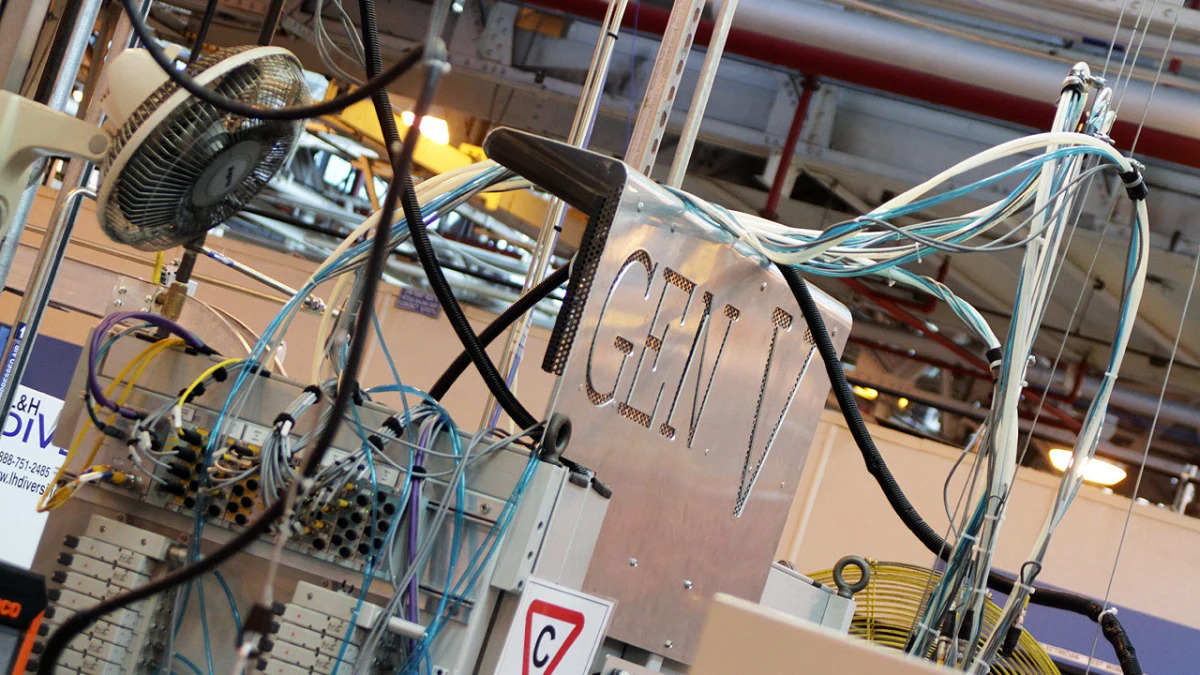

That's why we enjoyed our tour of General Motors Powertrain Tonawanda Engine Plant in Buffalo, New York. We've seen plenty of engines dropped into cars. Watching people and machines build an engine, that got us interested. And not just any engine – this was the Gen V small-block we were witnessing the birth of. Or rather, hundreds of births during our few hours at the factory.

There have only been five small-block family members since 1955, and this latest is not only a rebirth of GM's signature engine for its reborn signature car, the C7 Corvette Stingray, but represents the rebirth of the company itself and the factory that makes it; the Gen V incorporates new internal technologies and new build technologies.

GM has invested $825 million since 2010 at Tonawanda for the engines it builds, $400 million of that specifically for the Gen V small block. Since 1938 the plant has built 70,967,249 engines, and will crank out – get it, "crank" – its 71-millionth engine this year. Our first thought on stepping onto the plant floor: "Modern Marvels, here we come."

If you prefer the picture tour, there's a captioned high-res gallery above if you click the lead photo, and a few videos below. Otherwise, read on...

The Tonawanda Engine Plant was built in 1937, designed by Albert Kahn – "The Architect of Detroit" – as a one-million-square-foot manufacturing facility for engines and axle assemblies. It began production in 1938 on Chevrolet's straight-six "Stove Bolt" engine, and a quick run through its history reveals these highlights:

- During the war years it assembled 14- and 18-cylinder Pratt & Whitney engines for planes like the P-47 Thunderbolt and B-24 Liberator

- It built the first Corvette's only engine, the 235 cid "Blue Flame" straight-six in 1953.

- It began production of the first small-block V8 in 1955, the 265 cid V8 "mouse" that was also destined for the Corvette. In the '55 Chevrolet Bel-Air, this same engine was known as the "Turbo Fire."

- In 1958 it began production on the original Big Block, the 348 cid "W Block" or Mark I. The last Big Block at Tonawanda was produced in 2009.

- It built performance engines in clean rooms, like the all-aluminum big block "ZL-1" for racing in 1969 and the performance motor for the Cosworth Vega – yes, the Chevrolet Vega – in 1975.

Before the economic downturn, the plant was doing more than a million engines a year and had 6,000 workers. Last year's production was 272,081 and the plant now employs 1,800 people, 1,500 of those coming on since 2009, more than 1,000 of them hired in the past year. After the investment to build the new engines, we're told it is now GM's most advanced plant. Oh, and it's been landfill-free since 2005, meaning it recycles 97 percent of its waste and the rest goes to the incinerator to produce energy.

In addition to those small Ecotec engines for the Malibu, Cadillac ATS and the new CTS, Tonawanda will eventually build all four versions of the Gen V small block: the EcoTec3 4.3-liter V6, 5.3-liter and 6.2-liter V8s for the new Chevrolet Silverado and GMC Sierra, plus the 6.2-liter LT1 engine for the C7 Corvette. Tonawanda will be the only plant to build the complete set.

They'll take spots in nine different GM models sold around the world by 2015, so GM has a lot of reasons to want to get it right. The company started with the way the engine was designed. The previous silo culture meant that design and manufacturing didn't communicate throughout the process, so the designers would plan an engine only to have the manufacturing representatives say, "We can't build it." For the Gen V there was a manufacturing rep embedded with the design team.

There's less automation on the Gen V assembly line than on previous lines, but smarter use of it. We were told that the previous EcoTecs had 45 footprinted jobs (workstations with people) while the Gen V has 105, but the flexible machines and processes mean that all four engines can be built on one line – the machines can perform their assigned tasks on any version of the Gen V block. On top of that, it used to be that if a machine needed to be moved and reconfigured to a new task it took weeks to get that done, with process engineers and tradespeople all figuring in the effort. The new machines, however, use programmable logic controllers and can simply be reprogrammed if they need to perform a new job. That can be done in a single shift.Flexible machines and processes mean that all four engines can be built on one line.

On one side of the factory, the arriving cast blocks and heads – there's no foundry at Tonawanda – go left-to-right, on the other side the cylinder head assembly goes right-to-left, and they meet in the middle at two lines where they are joined and the engine is finished.

The cast blocks and heads are first handed off to the "flying robots" that place them in Smart Drive CNC machines for machining, drilling and tapping, milling surfaces. There are 29 machining processes for blocks and 11 machining processes for heads, such as the cylinder boring machines that pass blocks through rough-to-fine cylinder finishes.

There are three different stations for checking blocks. The first is a cage containing four machines, with a robot to move each tested block through the routine. The central arm takes each block and places it in a stand where the threads are checked, then it's handed to another machine that plugs holes that were used to access deeper parts of the block during machining, then there's a leak test, and a final machine makes sure there are no filings or machined bits left in places like oil channels. Any type of Gen V block can be tested here, whereas previously these checks were handled one at a time and separate lines were required for six- and eight-cylinder engines.

Then there are two types of Coordinate Measuring Machines (CMMs) that run 24 hours a day: 12 Zeiss Accura CMMs and six Hommel Etamic Wavemove CMMs.

Each in the assembly process kicks out a part at a predetermined frequency, and the CMMs can be programmed to test a block for any specific process. The Zeiss' use computer-controlled probes to measure the dimensions of machined cylinder heads and engine blocks; they can check more than 11,000 data points within 2.5 microns. They are hooked into the computers at GM Powertrain's headquarters in Pontiac, MI, and engineers there can update, control and monitor the measuring processes in Tonawanda.

The Hommels use probes to measure the surface finish of machined heads and blocks, specifically looking for deviations like textural roughness and material waviness, down to less than a micron. The CMMs are calibrated daily and certified once a year.

A Track and Trace system for the blocks and heads uses databolts and laser-etched 2D codes to follow the assembly process for engines and parts. GM has used RFID tags before, but never at this level. Databolts that can store 2,048 bytes (2K) are installed on each block and head before machining, and they can tell "the exact time and place a block or head goes through each process." The only thing it can't tell is the name of the person at the machine in question. If a block should fail a test, such as the leak test, the databolt will ID it and it will be automatically set aside. It can also identify the blocks and heads built around it so that engineers can test to see whether the failure was just on that block or if a process has suffered a larger error.

Additionally, cameras placed throughout the line capture images of the 2D codes on block, heads and parts, and each image is tied to the build of each engine. We were told the result is that if you have a problem with a Gen V engine in a car you've bought, engineers can go back and trace every part and operation in that specific engine's build.If you have a problem with a Gen V engine ... engineers can go back and trace every part and operation in that specific engine's build.

Another big investment was the bank of three Smart Cell machines that install valve assemblies in the heads. Each machine replaces four machines and five people, and also enables the flexibility to build engines on one line. Two trays are filled with the parts needed for valve assemblies, and they're put on a conveyor. Two robotic arms deliver a palette with two trays and a head to the Smart Cell, where everything is checked with the databolts and 2D codes to make sure the right parts are being used on the right head. It then presses in valve seals, flips the head over, installs the intake valves, installs the exhaust valves, flips the head back over, installs the valve springs and keys up the valves. It takes 40 seconds to install all 48 parts.

Further on, helium and a mass spectrometer are used to check for leaks in the high-pressure direct-injection system. Each of the DI system's stainless steel lines is covered by a sealed clamp that forms a vacuum collection chamber. Helium is run through the system at 60 psi, and any that escapes gets sucked into the filters of a mass spectrometer that can detect flow of less than one part per billion. Even though the helium test is run at 60 psi and the DI system runs at up to 2175 psi, if a helium atom – the second smallest element – cannot trigger a failure of the leak test, it is presumed that the much larger fuel molecule will not leak even at the higher pressure.

The completed engines are then cold tested – Tonawanda stopped hot testing 16 years ago, cold testing being a safer alternative since it doesn't require fuel. It takes 90 seconds to test an engine on one of the three stands while the engine is hooked up to a servo motor that cranks it over at up to 2,000 rpm to test 1,600 measurements. The results of tests of high- and low-speed NVH, vacuum on intake, pressure at exhaust and oil pump pressure, among others, are registered as waveforms on the results monitor.Tonawanda can put out 4,000 engines a day.

Assuming the engine has made it this far, it is put on a palette and sent to Plant 4 to find a good home in a GM product, while its databolt is cleared and sent to the front of the line for reuse. Tonawanda runs three shifts a day, five days a week, and when the lines are fully operational they'll be building about 1,600 Gen V engines a day, with a max capacity of 2,000 if needed. Factor in the EcoTecs made at Plant 1 and Tonawanda can put out 4,000 engines a day.

It was time well spent watching the 'little things' that make our cars what they are and make us feel the way we do about them, even though there was nothing we could drive off the lot at the end of it. As plant manager Steve Finch says about his domain, "We don't make cars, we make 'em go."

Sign in to post

Please sign in to leave a comment.

Continue