Volkswagen Passat Ling Yu - Click above for high-res image gallery

In many ways the automotive world – like most industries – runs like 19th century Europe: wars, skirmishes, diplomacy, assignations, shifting alliances, double dealing, imperialism. Everybody wants something the other guy has, and they'll occasionally exercise some ruthless tactics to get it. Of course, the obverse also happens: warring sects can work together to a singular end. That's what happens at the California Fuel Cell Partnership (CFCP), which we recently visited for a drive of the Chinese-engineered Volkswagen Passat Ling Yu and the smell of hydrogen in the morning.

Follow the jump to see what CFCP says the near future is going to be like.

Photos Copyright ©2009 Jonathon Ramsey / Weblogs, Inc.

The California Fuel Cell Partnership, tucked between train tracks and the highway in a quiet part of Sacramento, is where 31 government and industry partners work together to prepare that most elemental of elements for mass consumption. Volkswagen is one carmaker – alongside Chrysler, Daimler, GM, Honda, Hyundai, Nissan and Toyota – that works with CFCP on H2 vehicles.

VW isn't new to this. The company joined the CFCP in 1999 and began work on its high-temperature fuel cell. At the time, there were very few fuel cell vehicles on the road, the fuel cell pack in the Honda FCX weighed almost 500 pounds, and according to John Tillman, head of the CFCP, "We hoped to get down the road" (probably trying to get to one of the two fueling stations to be found anywhere on the planet). Today, they've got a fleet of about 300 vehicles and are working to build up to 100 fueling stations along California highways by 2010.

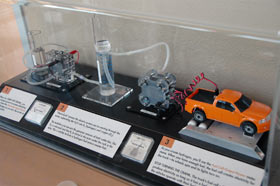

Nor is hydrogen the only alternative fuel on VW's research plate. At the center of the program is a source-to-powertrain tree that at first glance is so convoluted it could have been lifted from medieval royalty. Under "Source" come the fossil fuels – crude oil, coal, uranium, natural gas – and the renewable fuels: wind, water, solar, geothermal and biomass. Energy carriers derived from those include electric, hydrogen, gasoline, diesel, coal-to-liquid, natural gas-to-liquid, biomass-to-liquid and biogass. Finally, the powertrain options that run off them could be a fuel-cell with electric motor, battery with electric motor or conventional ICE. What that means as far as things you can put a key in and drive – or, at least, ones that researchers can drive – are the diesel-engined Jetta Blue TDI and Passat BlueMotion, the Passat TSI EcoFuel, the Touran CCS (Combined Comubstion System) and the automaker's Twin Drive plug-in diesel hybrid prototypes. VW is also developing SynFuel from natural gas and SunFuel engines that run on gas made from biomass and cellulose-ethanol. So, what we have is a 12-course meal of energy substitutions.

Our trip to the CFCP was for a sampling of the Passat Ling Yu, used to chase cyclists and runners during the 2008 Olympics. The prototype was developed in China with students and researchers at Tongji University, which was establised by Germans in 1907 as a medical school. The Passat Ling Yu is two generations old, having been unveiled in 2007, and uses the fourth-generation low-temperature fuel cell (LTFC) technology that was developed at the university. VW has been supplanting that for the high-temperature fuel cell stack (HTFC) it's developing and was used in the Tiguan Hymotion and Touran HyMotion. The more efficient HTFC operates at a higher temperature, and so needs less cooling machinery. The benefits are that it's more compact and less expensive.

We actually thought a day in the older vehicle would be convenient because it would help us establish a reference point and let us know how big the leaps are between generations. (If someone showed you a 1937 Victrola Talking Machine and told you it was two generations old, you wouldn't expect them to show up with an iPod next year.)

The Passat gets an 88 kW electric motor located on the front axle. It's powered by a stack of batteries beneath the rear seats, which are in turn juiced up by a 55 kW hydrogen fuel cell stack in the floor of the car. With 155 lb-ft of pull, the Ling Yu gets to 62 mph in 15 seconds, has a top speed of about 90 mph and a range of up to 146 miles. The CFCP figures that no hydrogen car will be ready for retail until it gets 300 miles between fill-ups, and the fuel cells themselves need to last 150,000 miles. They may be right, but on our visit, we wouldn't be going anywhere near that far.

Get in the Passat and... it's a Passat. Brown, spacious VW-ness. To turn the key is to call a mid-range, turbine-like whine into being. If the A/C is on and the car needs a little goose, the compressor will come on. Otherwise, that's it. If you're conversing with passengers and thinking about driving, you won't notice anything until the compressor bellows.

Put the car in gear, press the gas, and you start moving with just a slight rumbling from the fuel cell and bits under the floor. The whine, however, doesn't change. Sure, it takes 15 seconds to get to 60 mph, and in our other guise of piloting Bugattis and Porsches, that sounds like a Permian Age, but it was never frustrating. True, we kept to city streets, but we never noticed cars hankering to get around us – and after all, a Chevy Aveo takes almost that long.

The Ling Yu is utterly fine on the move. About the only thing to take note of, and that's only if you're interested, is the console screen that indicates the three paths of energy flow between the electric motor, batteries and fuel cell stack. The slightly rumbling floor was a feature during every acceleration, and there were little noises that peeped and thudded every so often, but these are the kinds of things you get when you drive an experimental vehicle.

It would be misleading to spend too much time writing about actually driving the Ling Yu. It isn't the fastest thing in the world, nor is it the slowest. It hums instead of revs. It rides fine. It stops fine. Oh, there is this bit: when you stop and shut it down, it emits an irate, hovercraft-like roar as the compressors expel water from the fuel cell stacks, eventually followed by the last sputterings of liquid flying out of the chromed tips that sounds like you're swigging the final drops of a milkshake up the straw.

But the point is this: driving the Passat Ling Yu is like, well, driving a Passat. Albeit a detuned one.

The full story doesn't make sense, though, until these other stories make sense: getting hydrogen efficiently and building the infrastructure. VW bills the Passat Ling Yu as "a sustainable solution for the future of individual mobility," but that won't be the case until the boffins figure out how to get more energy from hydrogen than it takes to get the hydrogen in the first place.

VW has placed its fuel programs in the wheel-to-well context, basing the CO2 emissions calculus at the beginning: primary energy demand (PED). The company's own chart measuring PED against CO2 has a sailboat in the lower left corner and a fuel cell vehicle (from electrolysis) in the upper right corner straddling the other middling options. But the fuel cell vehicle comes with an asterisk: that happens in 2015. This adds perspective to the company's claim that its high-temperature fuel cell won't be affordable and commercially ready until 2020.

The CFCP's Tillman said it is working on two approaches to extracting hydrogen: doing so with completely clean energy like solar or wind, and conducting electrolysis after the water has been pressurized.

"Electrolysis is dirty," Tillman said. "Water doesn't compress much, just a couple of percent. If you pre-pressurize the water to 5,000 or 10,000 psi and do electrolysis at that pressure, you get hydrogen at very close to the same pressure and [the process is] much more efficient. You don't have to compress the hydrogen. No one's done it on a large scale before and it's not really understood yet. It's difficult, but it's doable. If they pull it off then you've got something."

You have something, yes – but you still don't have a hydrogen infrastructure. In addition to the tens of pumps that the CFPC is lobbying to have built, Tillman believes home refueling could be the way to connect the infrastructure gap. "Honda has a home fueler and VW is working on one," Tillman said, "and we have our own home fueler concept."

So while we took a spin in the world of tomorrow with the Passat Ling Yu – and its mild driving habits make it a lot like the world of today – there remain a fair number of tomorrows before it can be called "everyday". The CFCP is committed to putting hydrogen on the board and in play, and the Passat Ling Yu, and Touran and Tiguan HyMotions, are worthy pieces.

As for that infrastructure, we got a little closer to home fueling when we discovered half of the Shell conventional gas station a few blocks from where we were had been torn down and replaced with a hydrogen fueling station. Hydrogen is here, and when it decides to show itself to the masses, certainly one of the badges it will wear is "VW".

As we listened to the compressor whine of the hydro-fleet after our test drives, DriverSide colleague Alison Lakin remarked, "Sounds like the future." It feels, though, a lot like today.

Photos Copyright ©2009 Jonathon Ramsey / Weblogs, Inc.

Sign in to post

Please sign in to leave a comment.

Continue