In his ongoing fight against the local police force, Doug Odolecki is armed with two pieces of equipment.

Standing on a sidewalk in Parma, OH, he holds a hand-written cardboard sign in his hands that warns motorists of a DUI checkpoint that law-enforcement officers have set up about a half mile up State Road. It reads: "Checkpoint ahead! Turn now!"

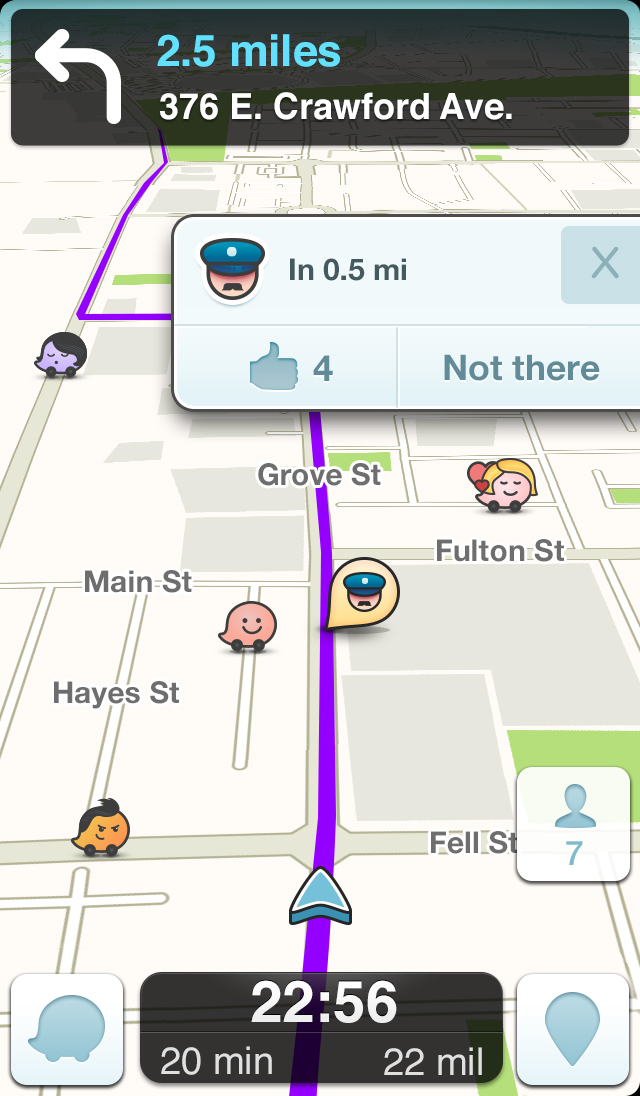

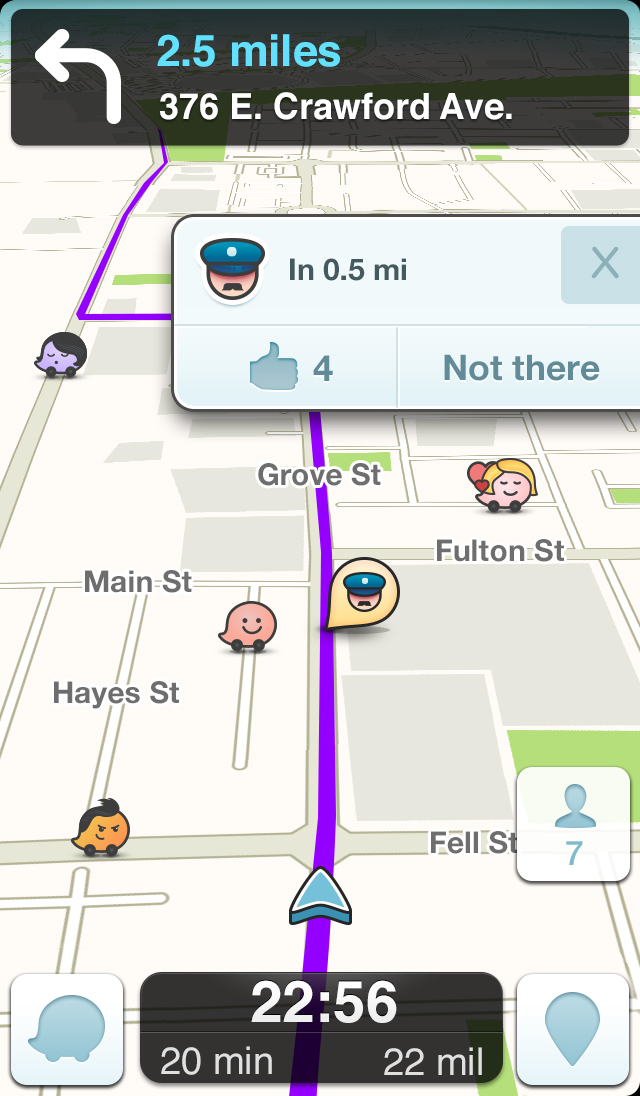

He keeps his smartphone nearby. In these situations, which are frequent, he likes to use the video feature to record his interactions with police officers. And he likes to use the Waze app to alert as many motorists as possible to the checkpoint ahead. His success can be fleeting.

"I'd be standing near the checkpoint sometimes, and I put it on the Waze app, and ten minutes later, it's gone," Odolecki said. "I put it on again, and it's gone again. There's a cop with a Waze app, and when he sees me there, he's deleting my posts."

The legality of his methods, both the old-fashioned and the new, are under considerable scrutiny.

Recent court rulings have indicated the First Amendment protects citizens' rights to warn motorists of traffic-enforcement activities by flashing their headlights at oncoming cars or taking other similar actions. But that hasn't stopped police officers from citing motorists for alleged improper conduct.

Now Waze adds a new dimension in the fight over law-enforcement location information. The traffic app helps millions of motorists navigate around traffic delays with real-time, crowd-sourced information. It also contains a feature that lets drivers pinpoint the location of speed traps with the push of a button.

Earlier this month, the National Sheriffs' Association expressed concerns about that feature, noting that criminals could use its precision to either avoid detection or, worse, ambush police officers. "It's a tool for people to do wrong," John Thompson, the organization's deputy executive director, said.

The National Sheriffs' Association asked representatives from Google, which owns Waze, to discontinue the police-location feature. So far, Google has left it intact. Overtures for a meeting on the topic have been rejected.

In some ways, this argument is nothing new. Motorists have sought an edge in evading traffic enforcement since the dawn of the automobile, and information has always been at the center of those efforts. CB radios, radar detectors are the forefathers of Waze.

In other ways, Waze represents a powerful new battleground over how that information is controlled, accessed and disseminated. At least for now, motorists are winning.

Courts: Flashing Headlights Constitutes Protected Speech

While Waze has yet to be examined in court, the legality of flashing headlights to warn motorists of speed traps has been affirmed in two recent court rulings.

On the afternoon of November 17, 2012, Michael Elli was driving northbound on Kiefer Creek Road in Ellisville, MO when he passed police officers conducting traffic enforcement. He flashed his headlights to warn oncoming motorists.

An officer cited him under a provision of the city code that prohibits flashing signals except on specified vehicles. On the citation, the officer wrote that flashing "lights on certain vehicles prohibited. Warning of radar ahead." Elli faced the prospect of a $1,000 fine. When he pleaded not guilty in municipal court, the judge became agitated, according to court records, and asked Elli if he had "ever heard of obstruction of justice."

Soon after, though, the prosecutor dropped the charge. But Elli sued in civil court, contending that his First Amendment right to free speech had been violated. At a preliminary injunction hearing, US District Judge Henry Autrey ruled in his favor, saying the headlight communication suggested that drivers should conform with the law, and that Ellisville's efforts to detain and cite drivers who flashed their headlight had a "chilling effect" on free speech.

That echoed the ruling of a circuit court judge in Florida who ruled that flashing headlights to warn motorists of police activity constituted protected speech. His ruling stemmed from the case of a Lake Mary, FL, resident who was ticketed in August 2011.

"If the goal of the traffic law is to promote safety and not to raise revenue, then why wouldn't we want everyone who sees a law enforcement officer with a radar gun in his hand, blinking his lights to slow down all those other cars," Judge Alan Dickey said.

In the wake of the ruling, the Florida State Patrol stopped writing tickets for headlight-flashing offenses and the state legislature eventually passed a law that acknowledged flashing headlights constituted protected communications.

If those rulings count as successes for strengthening motorists' rights, they come with the caveat that despite the precedents, the police practice of ticketing motorists for flashing their headlights continues.

Only four months after the ruling in the Ellisville, another driver, Jerry L. Jarman Jr., was ticketed in Grain Valley, MO, for flashing his lights. He stood accused of "interfering with radar," according to his summons. Jarman instead sued, and last month he secured a settlement with the town of Grain Valley, which repealed a city ordinance that allowed officers to ticket motorists for headlight flashing.

Just last week, the American Civil Liberties Union settled a similar case in Smyrna, Del., where the town's police chief issued a memo of understanding that a traffic stop cannot be made solely on the flashing of headlights to warn of a speed trap.

Though their argument has prevailed, it's ultimately left to the ACLU to play a town-by-town game of legal whack-a-mole: When one case has been settled, another appears elsewhere.

Waze Could Aid Drunk Drivers In Avoiding Law Enforcement

Though he's careful to emphasize that speeding kills, Thompson acknowledges there's a certain gamesmanship in otherwise law-abiding drivers finding ways to avoid speed traps.

But he fears the Waze app will be used to skirt more serious offenses. If it hasn't happened already, he envisions a time when drunks will stumble out of bars and use the app to plot a route home that accounts for the location of police officers.

"I hate to say it, but the day we find out for sure that someone went this way or that way and used the Waze app and killed that mother and child, we'll know we could have saved those lives if we had just done something," he said. "That day is coming. The sad thing is, in my time, I've seen how we react to things, and in our society, it takes a tragedy or disaster to move on something."

Judges could view communications that alert drunks to checkpoints differently than the ones that motorists send via flashing headlights. A lynchpin in the Elli v. Ellisville ruling was that his flashing headlights sought to bring other motorists into conformity with the law; in drunk-driving cases, Waze communications may encourage the opposite. One case that could provide clarity on whether those free-speech rights extend to warning about DUI checkpoints involves Odolecki.

Judges could view communications that alert drunks to checkpoints differently than the ones that motorists send via flashing headlights. A lynchpin in the Elli v. Ellisville ruling was that his flashing headlights sought to bring other motorists into conformity with the law; in drunk-driving cases, Waze communications may encourage the opposite. One case that could provide clarity on whether those free-speech rights extend to warning about DUI checkpoints involves Odolecki.

The 44-year-old Parma, OH resident runs the Greater Cleveland chapter of Cop Block, a national nonprofit organization committed to seeking greater police accountability and support for victims of police abuses. During frequent outings around the city and its suburbs, he warns motorists of DUI checkpoints and videotapes his interactions with police officers.

On a late-spring night last June, Odolecki received a citation for obstructing official business and delaying the performance of a public official. He maintains he was several blocks away from the actual checkpoint and did nothing more than hold his sign.

"Our position is very simple," says John Gold, his Toledo-based attorney. "He's not at the checkpoint, so he's not interfering, and he has no control over what people do or don't do. ... And turn now? Guess what. They're allowed to turn. He's not suggesting these people do anything they're not already legally entitled to do."

Nor is Odolecki the only one who's issuing warnings. In fact, the police department does that itself.

In 1990, the US Supreme Court examined whether sobriety checkpoints posed an unreasonable search and seizure of citizens, which would violate the Fourth Amendment. The court ruled the state's interest in stopping drunk drivers outweighed lesser privacy intrusions.

The 6-3 decision in Michigan State of Police v. Sitz was a victory for law enforcement, but it also restricts the scope of the checkpoints. State courts have interpreted the ruling to mean the roadblocks are legal only if they sufficiently focus on stopping drunk driving and not generating revenue from more minor traffic offenses. And because the Supreme Court ruled temporary roadblocks present a greater surprise – and thus greater intrusion – many states, including Ohio, require police departments post advance notice of checkpoint locations.

Odolecki views his role as making sure police adhere to those requirements. He cites statistics obtained from Freedom of Information Act requests that show that during their past four DUI checkpoints, Parma police wrote 254 citations for seat-belt violations, which are secondary infractions.

"Anybody who didn't get a primary violation and still paid that, they got ripped off," Odolecki said. "The cops say these are about safety, but I say it's a money grab. If it was truly about safety, they'd do roving patrols because they're more effective. ... The checkpoints, they're a lazy way to do things, but they're a way for everybody to make money. These officers all make overtime to man those checkpoints. You're paying the road department overtime to set up cones. It's a money grab."

He faces a jury trial starting June 2.

Nefarious Uses For Waze Abound

In objecting to Waze, Thompson says it's not about the money. "If we were worried about that, we'd be busting them with red-light or speed cameras," he said.

The National Sheriffs' Associations fears the app will give terrorists and more hardened criminals the ability to target officers – that there will be ambushes like the one in New York in late December, in which Officers Wenjian Liu and Rafael Ramos were gunned down as they sat in their patrol car.

Such attacks are on the rise. Nationwide, 15 police officers were killed in ambush-style assaults in 2014, according to the National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial Fund, the most since 1995. By using Waze, criminals could precisely target officers who might be in more vulnerable or isolated locations.

But if Waze can be used to target, it can also be used to avoid detection. Thompson said he's already fielded reports that drug dealers in Florida are using the app to hide when police officers are in the area and he believes organized crime will find similar advantages.

In addition to marking the whereabouts of police officers on the app, an additional feature allows drivers to write a comment that appears alongside their geo-location tag. Could such a feature be used to note to detail the police activity?

"If someone hits that police button, they can type in whatever they want, 'SWAT team assembling' or 'undercover cops hanging out there,'" Thompson said. "Why do we want to risk lives by someone knowing that? ... Most people don't understand the ramifications here. As more people use this app, it's going to be more apparent, and when it takes hold, it will be a nasty tool."

Google did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

Thompson is hopeful the company will sit down and reach an agreement with law-enforcement officials on what's acceptable for Waze, and it's unclear whether the National Sheriff's Association would pursue legal action to thwart Waze.

"Until we sit down and talk with them, we don't know what options there are," he said. "We want the whole police button gone, but maybe there's a happy medium. We don't know if we can't talk."

If there's no recourse for preventing people from using the police-location features outright, some officers have found a partial solution. In Miami, hundreds of law-enforcement agents have joined Waze and are supplying a deluge of bogus information on their whereabouts to dilute the app's accuracy. In Ohio, as Odolecki observed, some officers are removing location information as fast as users can post it.

Should the issue reach the courts, it could take years to resolve. By then, the results may not matter. Technology is always one step ahead.

Related Video:

Standing on a sidewalk in Parma, OH, he holds a hand-written cardboard sign in his hands that warns motorists of a DUI checkpoint that law-enforcement officers have set up about a half mile up State Road. It reads: "Checkpoint ahead! Turn now!"

He keeps his smartphone nearby. In these situations, which are frequent, he likes to use the video feature to record his interactions with police officers. And he likes to use the Waze app to alert as many motorists as possible to the checkpoint ahead. His success can be fleeting.

"I'd be standing near the checkpoint sometimes, and I put it on the Waze app, and ten minutes later, it's gone," Odolecki said. "I put it on again, and it's gone again. There's a cop with a Waze app, and when he sees me there, he's deleting my posts."

The legality of his methods, both the old-fashioned and the new, are under considerable scrutiny.

Recent court rulings have indicated the First Amendment protects citizens' rights to warn motorists of traffic-enforcement activities by flashing their headlights at oncoming cars or taking other similar actions. But that hasn't stopped police officers from citing motorists for alleged improper conduct.

Now Waze adds a new dimension in the fight over law-enforcement location information. The traffic app helps millions of motorists navigate around traffic delays with real-time, crowd-sourced information. It also contains a feature that lets drivers pinpoint the location of speed traps with the push of a button.

Earlier this month, the National Sheriffs' Association expressed concerns about that feature, noting that criminals could use its precision to either avoid detection or, worse, ambush police officers. "It's a tool for people to do wrong," John Thompson, the organization's deputy executive director, said.

The National Sheriffs' Association asked representatives from Google, which owns Waze, to discontinue the police-location feature. So far, Google has left it intact. Overtures for a meeting on the topic have been rejected.

In some ways, this argument is nothing new. Motorists have sought an edge in evading traffic enforcement since the dawn of the automobile, and information has always been at the center of those efforts. CB radios, radar detectors are the forefathers of Waze.

In other ways, Waze represents a powerful new battleground over how that information is controlled, accessed and disseminated. At least for now, motorists are winning.

Courts: Flashing Headlights Constitutes Protected Speech

While Waze has yet to be examined in court, the legality of flashing headlights to warn motorists of speed traps has been affirmed in two recent court rulings.

On the afternoon of November 17, 2012, Michael Elli was driving northbound on Kiefer Creek Road in Ellisville, MO when he passed police officers conducting traffic enforcement. He flashed his headlights to warn oncoming motorists.

An officer cited him under a provision of the city code that prohibits flashing signals except on specified vehicles. On the citation, the officer wrote that flashing "lights on certain vehicles prohibited. Warning of radar ahead." Elli faced the prospect of a $1,000 fine. When he pleaded not guilty in municipal court, the judge became agitated, according to court records, and asked Elli if he had "ever heard of obstruction of justice."

Soon after, though, the prosecutor dropped the charge. But Elli sued in civil court, contending that his First Amendment right to free speech had been violated. At a preliminary injunction hearing, US District Judge Henry Autrey ruled in his favor, saying the headlight communication suggested that drivers should conform with the law, and that Ellisville's efforts to detain and cite drivers who flashed their headlight had a "chilling effect" on free speech.

That echoed the ruling of a circuit court judge in Florida who ruled that flashing headlights to warn motorists of police activity constituted protected speech. His ruling stemmed from the case of a Lake Mary, FL, resident who was ticketed in August 2011.

"If the goal of the traffic law is to promote safety and not to raise revenue, then why wouldn't we want everyone who sees a law enforcement officer with a radar gun in his hand, blinking his lights to slow down all those other cars," Judge Alan Dickey said.

In the wake of the ruling, the Florida State Patrol stopped writing tickets for headlight-flashing offenses and the state legislature eventually passed a law that acknowledged flashing headlights constituted protected communications.

If those rulings count as successes for strengthening motorists' rights, they come with the caveat that despite the precedents, the police practice of ticketing motorists for flashing their headlights continues.

Only four months after the ruling in the Ellisville, another driver, Jerry L. Jarman Jr., was ticketed in Grain Valley, MO, for flashing his lights. He stood accused of "interfering with radar," according to his summons. Jarman instead sued, and last month he secured a settlement with the town of Grain Valley, which repealed a city ordinance that allowed officers to ticket motorists for headlight flashing.

Just last week, the American Civil Liberties Union settled a similar case in Smyrna, Del., where the town's police chief issued a memo of understanding that a traffic stop cannot be made solely on the flashing of headlights to warn of a speed trap.

Though their argument has prevailed, it's ultimately left to the ACLU to play a town-by-town game of legal whack-a-mole: When one case has been settled, another appears elsewhere.

Waze Could Aid Drunk Drivers In Avoiding Law Enforcement

Though he's careful to emphasize that speeding kills, Thompson acknowledges there's a certain gamesmanship in otherwise law-abiding drivers finding ways to avoid speed traps.

But he fears the Waze app will be used to skirt more serious offenses. If it hasn't happened already, he envisions a time when drunks will stumble out of bars and use the app to plot a route home that accounts for the location of police officers.

"I hate to say it, but the day we find out for sure that someone went this way or that way and used the Waze app and killed that mother and child, we'll know we could have saved those lives if we had just done something," he said. "That day is coming. The sad thing is, in my time, I've seen how we react to things, and in our society, it takes a tragedy or disaster to move on something."

Judges could view communications that alert drunks to checkpoints differently than the ones that motorists send via flashing headlights. A lynchpin in the Elli v. Ellisville ruling was that his flashing headlights sought to bring other motorists into conformity with the law; in drunk-driving cases, Waze communications may encourage the opposite. One case that could provide clarity on whether those free-speech rights extend to warning about DUI checkpoints involves Odolecki.

Judges could view communications that alert drunks to checkpoints differently than the ones that motorists send via flashing headlights. A lynchpin in the Elli v. Ellisville ruling was that his flashing headlights sought to bring other motorists into conformity with the law; in drunk-driving cases, Waze communications may encourage the opposite. One case that could provide clarity on whether those free-speech rights extend to warning about DUI checkpoints involves Odolecki.

The 44-year-old Parma, OH resident runs the Greater Cleveland chapter of Cop Block, a national nonprofit organization committed to seeking greater police accountability and support for victims of police abuses. During frequent outings around the city and its suburbs, he warns motorists of DUI checkpoints and videotapes his interactions with police officers.

On a late-spring night last June, Odolecki received a citation for obstructing official business and delaying the performance of a public official. He maintains he was several blocks away from the actual checkpoint and did nothing more than hold his sign.

"Our position is very simple," says John Gold, his Toledo-based attorney. "He's not at the checkpoint, so he's not interfering, and he has no control over what people do or don't do. ... And turn now? Guess what. They're allowed to turn. He's not suggesting these people do anything they're not already legally entitled to do."

Nor is Odolecki the only one who's issuing warnings. In fact, the police department does that itself.

In 1990, the US Supreme Court examined whether sobriety checkpoints posed an unreasonable search and seizure of citizens, which would violate the Fourth Amendment. The court ruled the state's interest in stopping drunk drivers outweighed lesser privacy intrusions.

The 6-3 decision in Michigan State of Police v. Sitz was a victory for law enforcement, but it also restricts the scope of the checkpoints. State courts have interpreted the ruling to mean the roadblocks are legal only if they sufficiently focus on stopping drunk driving and not generating revenue from more minor traffic offenses. And because the Supreme Court ruled temporary roadblocks present a greater surprise – and thus greater intrusion – many states, including Ohio, require police departments post advance notice of checkpoint locations.

Odolecki views his role as making sure police adhere to those requirements. He cites statistics obtained from Freedom of Information Act requests that show that during their past four DUI checkpoints, Parma police wrote 254 citations for seat-belt violations, which are secondary infractions.

"Anybody who didn't get a primary violation and still paid that, they got ripped off," Odolecki said. "The cops say these are about safety, but I say it's a money grab. If it was truly about safety, they'd do roving patrols because they're more effective. ... The checkpoints, they're a lazy way to do things, but they're a way for everybody to make money. These officers all make overtime to man those checkpoints. You're paying the road department overtime to set up cones. It's a money grab."

He faces a jury trial starting June 2.

Nefarious Uses For Waze Abound

In objecting to Waze, Thompson says it's not about the money. "If we were worried about that, we'd be busting them with red-light or speed cameras," he said.

The National Sheriffs' Associations fears the app will give terrorists and more hardened criminals the ability to target officers – that there will be ambushes like the one in New York in late December, in which Officers Wenjian Liu and Rafael Ramos were gunned down as they sat in their patrol car.

Such attacks are on the rise. Nationwide, 15 police officers were killed in ambush-style assaults in 2014, according to the National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial Fund, the most since 1995. By using Waze, criminals could precisely target officers who might be in more vulnerable or isolated locations.

But if Waze can be used to target, it can also be used to avoid detection. Thompson said he's already fielded reports that drug dealers in Florida are using the app to hide when police officers are in the area and he believes organized crime will find similar advantages.

In addition to marking the whereabouts of police officers on the app, an additional feature allows drivers to write a comment that appears alongside their geo-location tag. Could such a feature be used to note to detail the police activity?

"If someone hits that police button, they can type in whatever they want, 'SWAT team assembling' or 'undercover cops hanging out there,'" Thompson said. "Why do we want to risk lives by someone knowing that? ... Most people don't understand the ramifications here. As more people use this app, it's going to be more apparent, and when it takes hold, it will be a nasty tool."

Google did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

Thompson is hopeful the company will sit down and reach an agreement with law-enforcement officials on what's acceptable for Waze, and it's unclear whether the National Sheriff's Association would pursue legal action to thwart Waze.

"Until we sit down and talk with them, we don't know what options there are," he said. "We want the whole police button gone, but maybe there's a happy medium. We don't know if we can't talk."

If there's no recourse for preventing people from using the police-location features outright, some officers have found a partial solution. In Miami, hundreds of law-enforcement agents have joined Waze and are supplying a deluge of bogus information on their whereabouts to dilute the app's accuracy. In Ohio, as Odolecki observed, some officers are removing location information as fast as users can post it.

Should the issue reach the courts, it could take years to resolve. By then, the results may not matter. Technology is always one step ahead.

Related Video:

Sign in to post

Please sign in to leave a comment.

Continue