I cannot recall a point during my automotive career – or even the college days that came before – that didn’t include some flavor of mid-engine Corvette rumor. The hopeful scuttlebutt persisted for so long that I’d tuned it out completely by the time the C7 came out in 2014, and indeed that car proved to be so well-sorted dynamically that I assumed Chevrolet had “done a Porsche” and decided to stick with the Vette’s hereditary engine placement forever.

And then weird-looking prototypes made to look like an Australian-market Holden Maloo ute started showing up. Grainy UFO-quality spy photos taken through ridiculously long (but not long enough) lenses came soon after, and despite their lack of sharp focus, it soon became clear that the C8 Corvette would be the one that finally turned the endless rumors into reality. I’ve been scheming to get my hands on one ever since.

Such a complete rethink of the engine placement cannot happen without a clean-sheet approach to the suspension that supports each corner, so there’s every reason to expect the C8 will be completely fresh underneath. This Stingray is a 3LT with the Z51 suspension package, MagneRide dampers and a front suspension lift system. Let’s pull the wheels off and take a long look.

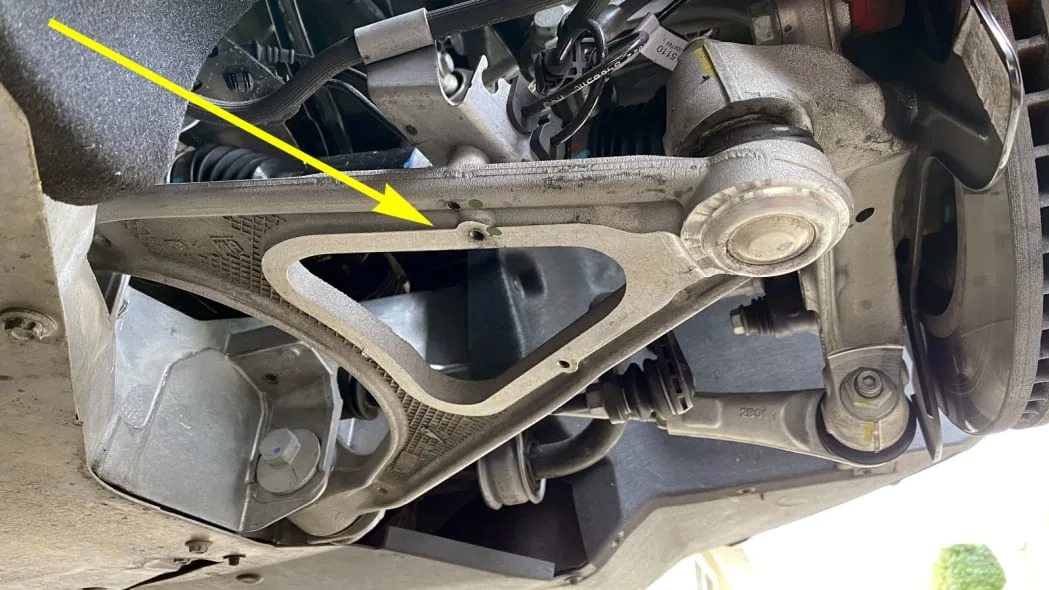

From here, the C8 Corvette doesn’t give away many of its secrets.

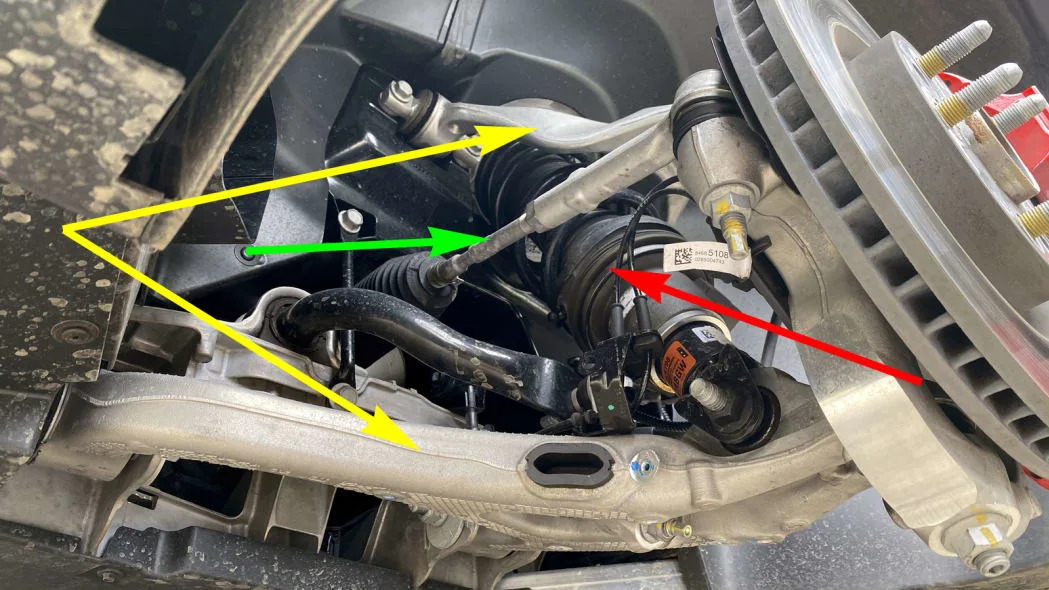

A prominent plastic shield (yellow arrow) utterly blocks the view from this angle, so it’ll have to come off. Its real purpose is twofold: deflect cooling air exiting the bumper ducts toward the caliper and rotor; and smooth the air flowing under the car as it passes across what is probably a lower wishbone.

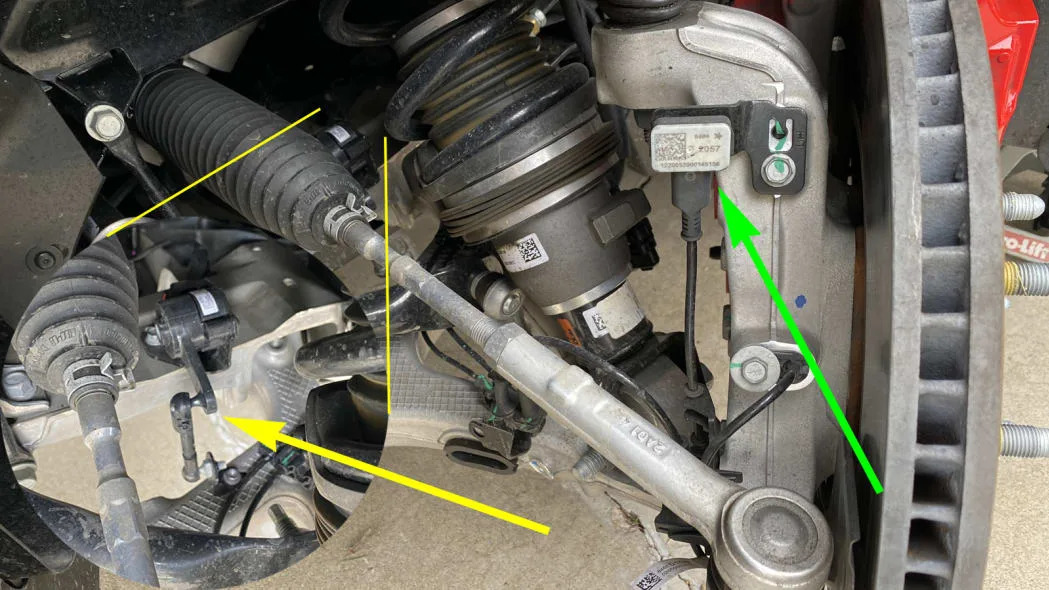

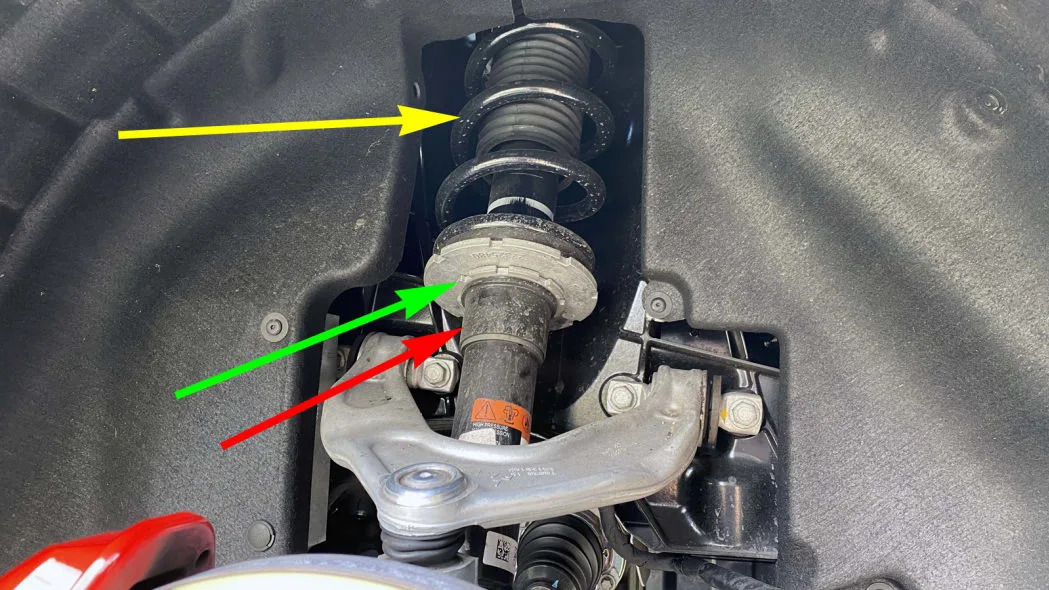

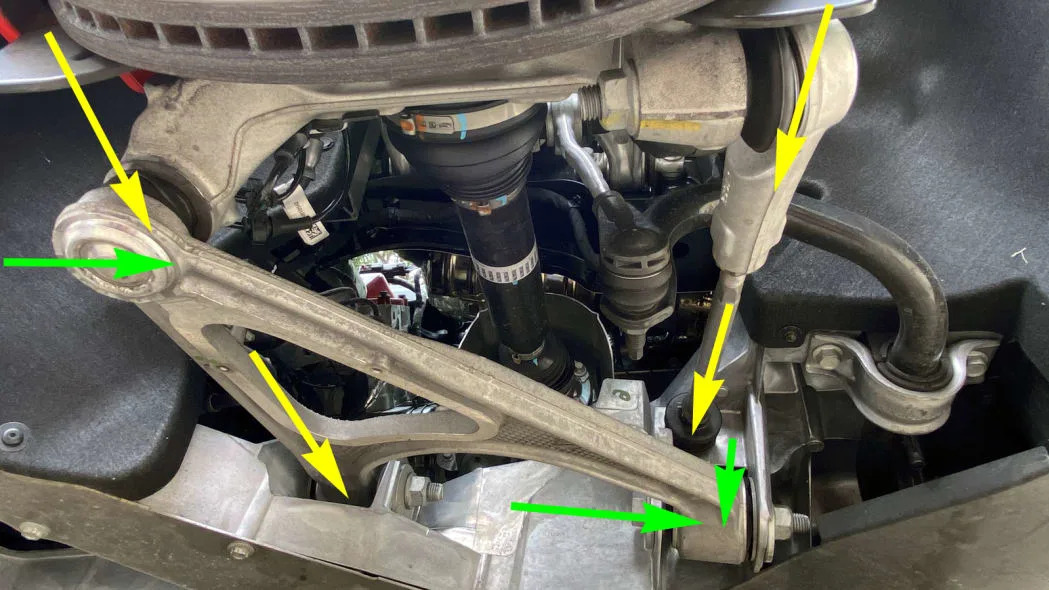

Now we can see the double-wishbone suspension (yellow) that was expected. The front-acting steering linkage (green) placement is no surprise, and the highly reclined front damper (red) is familiar, too.

But there’s a significant change visible here, too. Past Corvettes have ridden on a transverse composite leaf spring that spanned below the engine from the left to the right lower wishbones. That’s gone here.

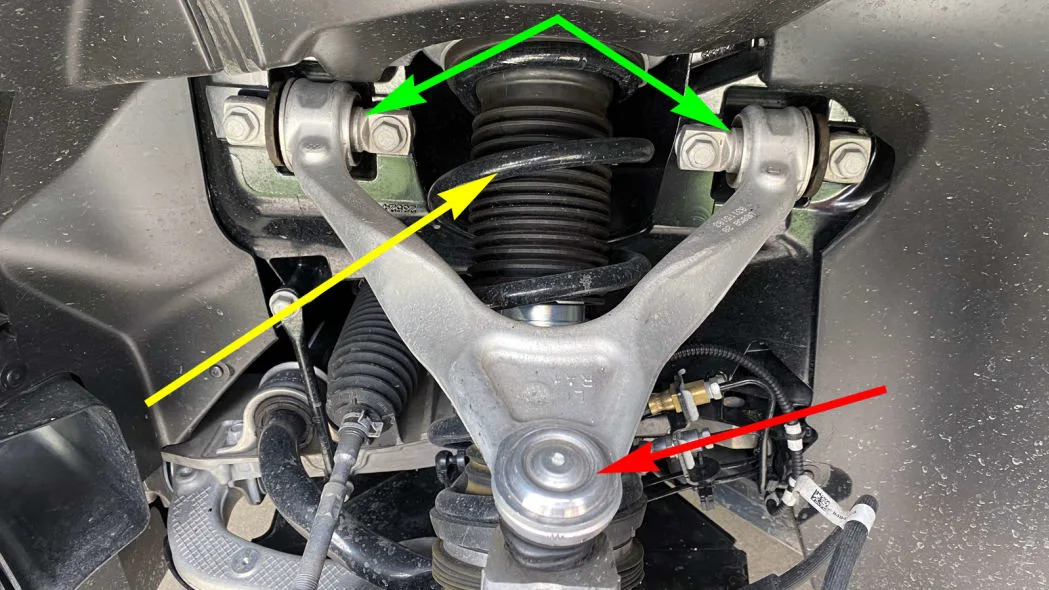

Instead, the C8 uses a much more conventional coil-over spring (yellow).

The aluminum upper wishbone, on the other hand, uses the same sort of tie-bar mounting (green) we saw on the C7. But the ball joint and steering knuckle fit together differently. The C7’s knuckle had the ball joint built into it and captured the arm from above, but here the ball joint (red) is part of the arm and sits atop the steering knuckle.

Because the bulky transverse composite leaf spring is history, the C8’s lower wishbone is able to have a much more distinct L-shape than the C7 ever could. This helps both ride and handling because each of the two inner pivot bushings can be more specialized.

The rear pivot bushing (yellow) is somewhat closely aligned with the lateral cornering loads that feed in from the outer ball joint and the tire contact patch, so it can be optimized to handle those loads. The job of the forward pivot (green) is more about bracing the wheel in the fore-aft direction and standing up to the longitudinal component of track-day curb-hopping and ordinary pothole strikes. Such rearward pulses at the tire turn into backward and outward tugs in this bushing, and a bit of softness and compliance up there won’t interfere with the business of cornering that’s primarily happening further back.

The stabilizer bar (yellow) routing is very simple, but the short connecting link (green) attaches to the suspension in a very clever way through an opening in the lower wishbone.

It’s all very tidy. Incidentally, the pinched-off look of the flattened end of the stabilizer bar gives away the fact that it’s hollow.

That ball-and-socket part (yellow) of that stabilizer bar mounting link is where its motion ratio must be measured, and that puts it right around 0.5-to-1 based on its position between the pivot axis to the lower ball joint. The coil-over damper mounting point’s motion ratio looks to sit at almost 0.8-to-1, but the spring-shock assembly is so steeply reclined that it can’t be ignored. Trigonometry has something to say about the overall result, so I’m prepared to lower that estimate to about 0.6-to-1 with the prodigious lean angle taken into account

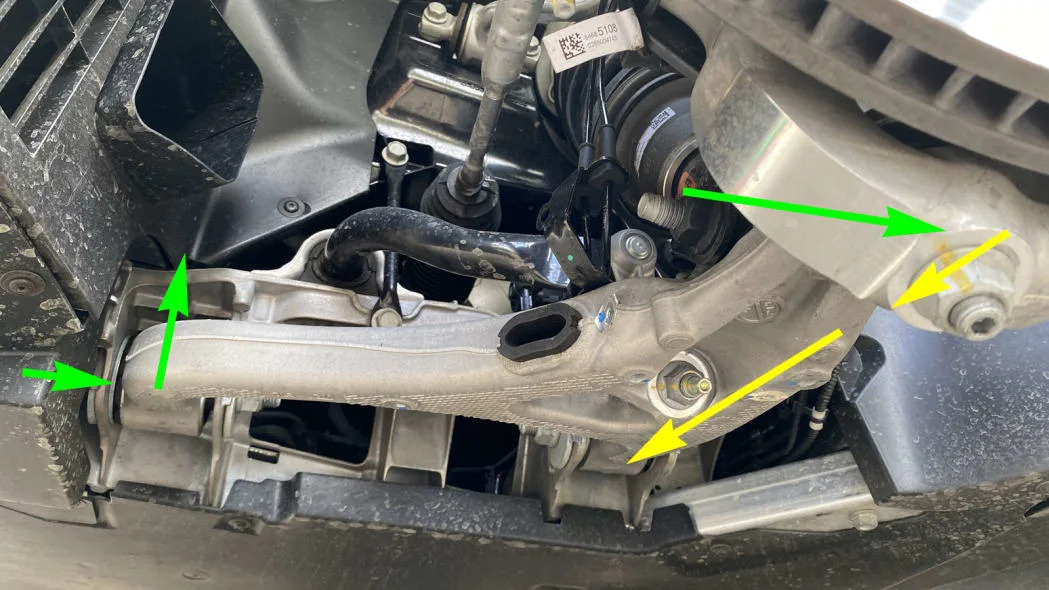

As one would expect, both legs of the C8’s lower wishbone are fitted with eccentrics to make alignment adjustments. But the same division of responsibilities that come with this arm’s L-shape should make adjustments more straightforward, too. The rear one will have a lot to do with camber, while the forward one will have the greatest bearing on caster.

The Z51 package is supposed to come with threaded shock bodies and manually adjustable lower spring seats that autocrossers can use to make corner-weight and even height adjustments.

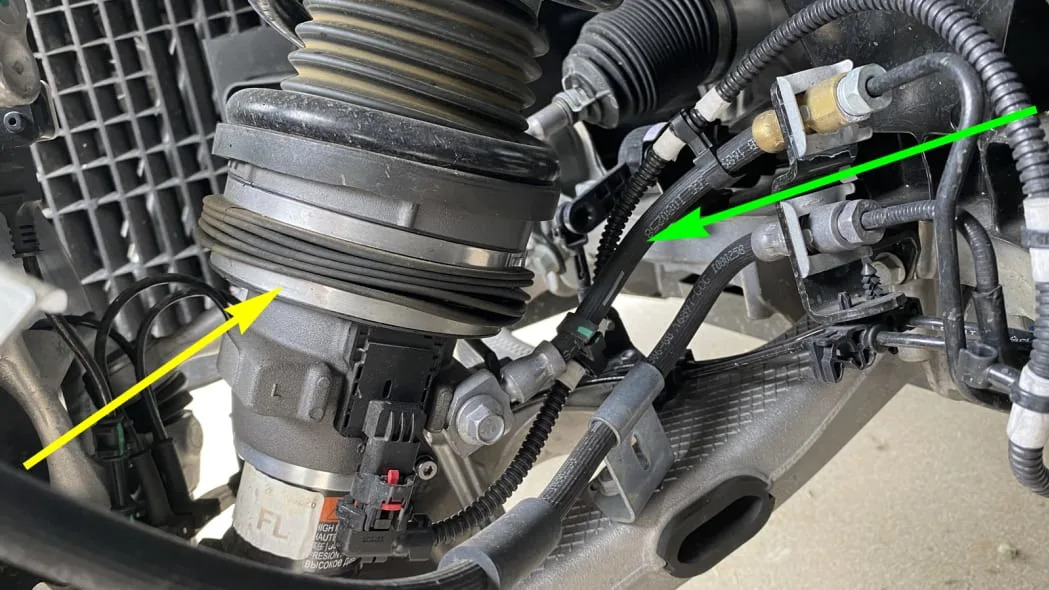

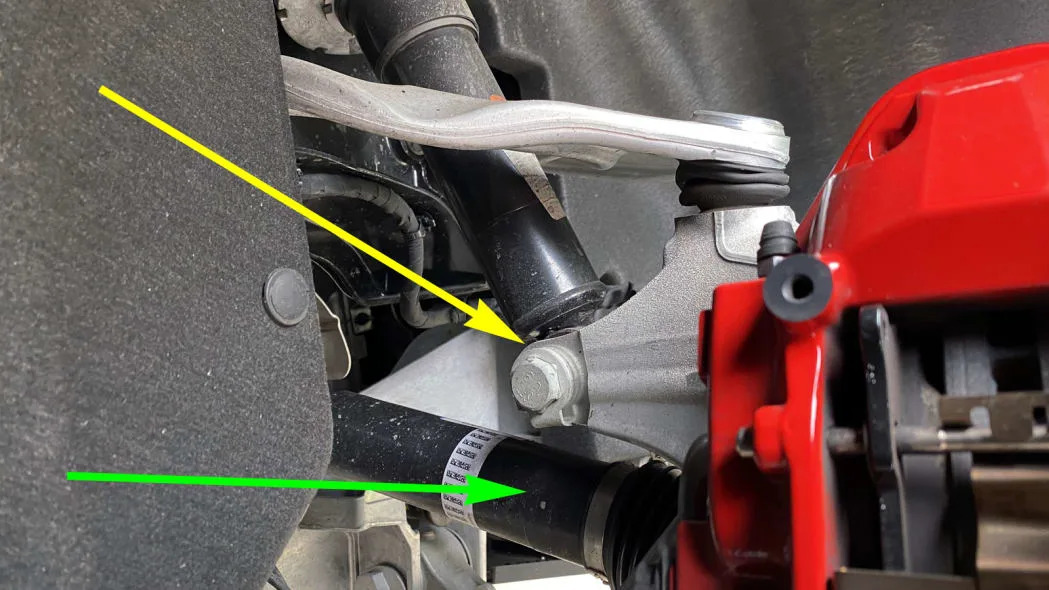

That’s absent here because this particular Z51 Stingray has been fitted with the optional front lift system, which amounts to a hydraulically-actuated lower spring seat that grows enough to raise the front bumper 40 millimeters (just over 1.5 inches.) It operates quickly using a hidden electrically-driven hydraulic pump and accumulator that feeds in pressure via a second hose (green) just above the brake line.

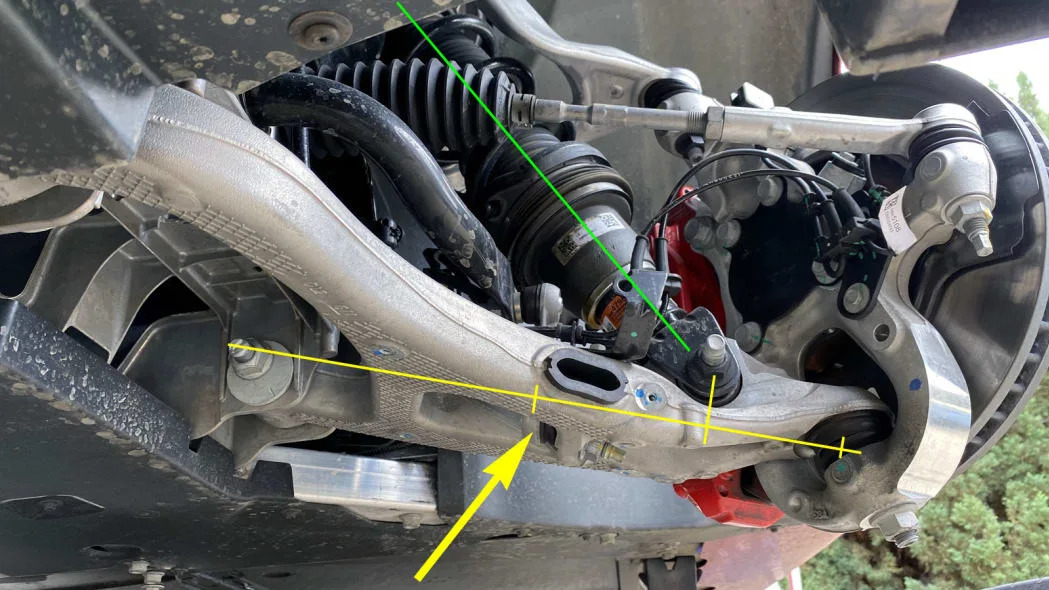

Here, the collapsed bellows (yellow) is a sign that the system is in the normal ride height position, something that the car automatically settled into whenever I switched off the engine. I must admit it makes the car look much better when parked than the McLaren GT, which retained its nose-up posture when I shut its motor down.

It can work that way here because the system is GPS linked so you can store locations you’ll visit more than once, and there’s no reason to hesitate to use the memory because up to 1,000 positions can be stored. My own driveway was a no-brainer, but so was the restaurant down the street I typically visit maybe once every other month. You’re prompted to save a given position whenever you engage the lift, and a simple flick of a steering wheel button is all that’s needed to say yes or no.

High-performance MagneRide adjustable dampers are available on the C8 as an option. These patented dampers appear on numerous high-level brands, and we most recently saw them on the Acura NSX Suspension Deep Dive.

Most adjustable dampers have internal valving that is tuned toward the stiff end of its performance spectrum, with the adjustability coming from an electronically adjustable bypass mechanism that diverts a variable portion of the fluid flow around the valve, thereby reducing the damping force that’s generated. More bypass, less stiffness; less bypass, more stiffness.

MagneRide dampers don’t work that way. They employ fixed valving with no variable bypass, with the adjustable damping force coming from a special magnetorheological fluid flowing through the fixed valving. The viscosity of the fluid itself can be altered by changing the strength of an electromagnetic field in the damper. Thicker fluid, more stiffness; thinner fluid, less stiffness.

All types of adjustable damper systems need to monitor the movement of the suspension so the computer can execute adjustments, but no two sensor layouts and control algorithms are exactly alike – even between different cars that both use MagneRide. Here we can see a suspension position sensor (yellow) mounted to the C8’s lower arm, and a hub accelerometer (green) mounted to the steering knuckle.

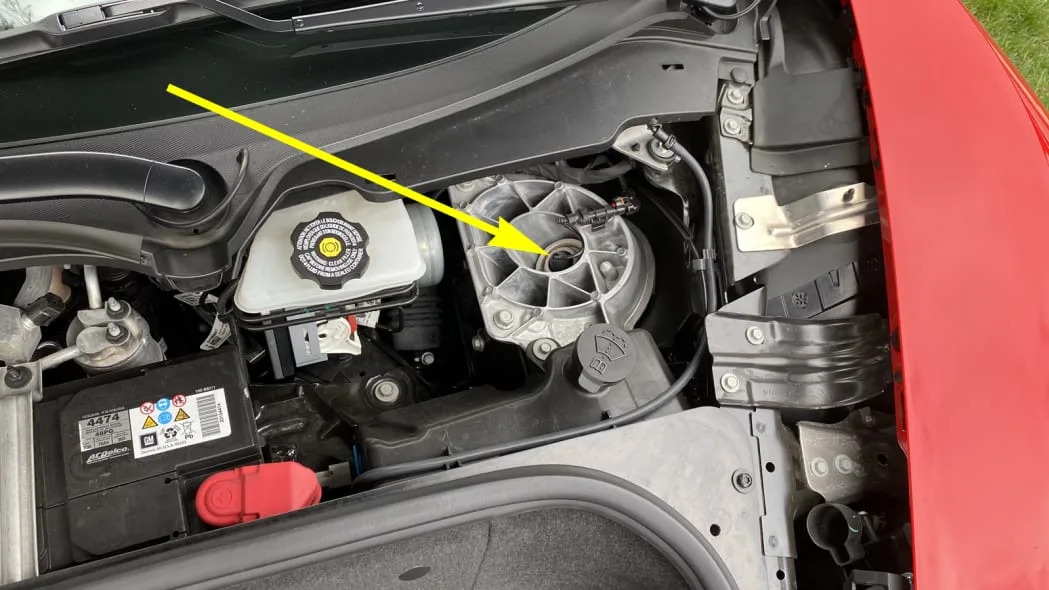

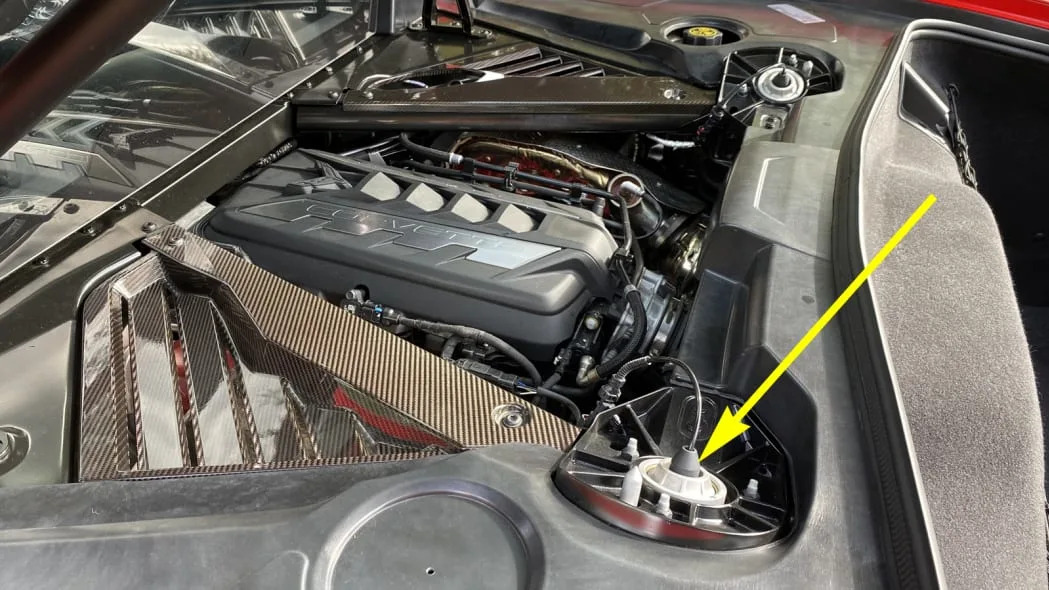

The upper shock towers are exquisite-looking aluminum pieces, but the thing to notice here is the slender control wire (yellow) that emerges from the uppermost end of the MagneRide damper’s shaft.

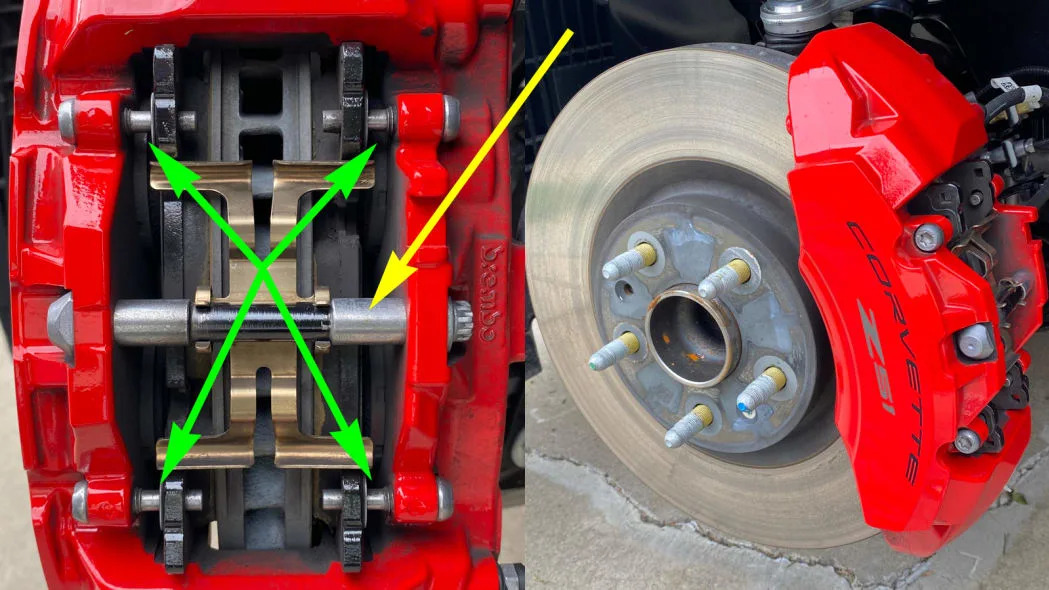

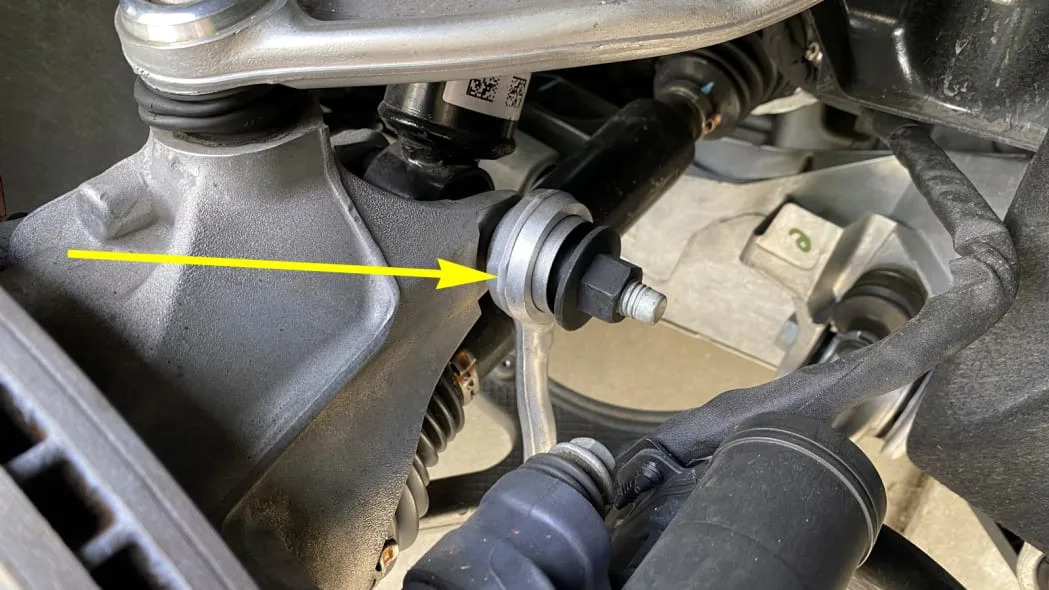

Four-piston fixed Brembo calipers make up the Z51’s front brakes. They use an open window design that eases pad changes, but with a removable bridge bolt (yellow) that keeps the structure stiff despite that open window. You have to remove that to get the pads out, but you’ll also need to remove four screwed-in pad positioning pins (green) that look a bit more fiddly than the window-spanning skewer-style pins we usually see.

The rotors are one-piece cast iron affairs that are neither drilled nor slotted, and their perimeter vents don’t extend through to the hub area. I can’t help thinking there’s a lot of room for a marketable performance upgrade when the inevitable Z06/Z07, Gran Sport and other hot-rod versions come along.

The brake rotor may be blocking most of it, but we can already see an upper wishbone and its tie bar-style mounts at the rear.

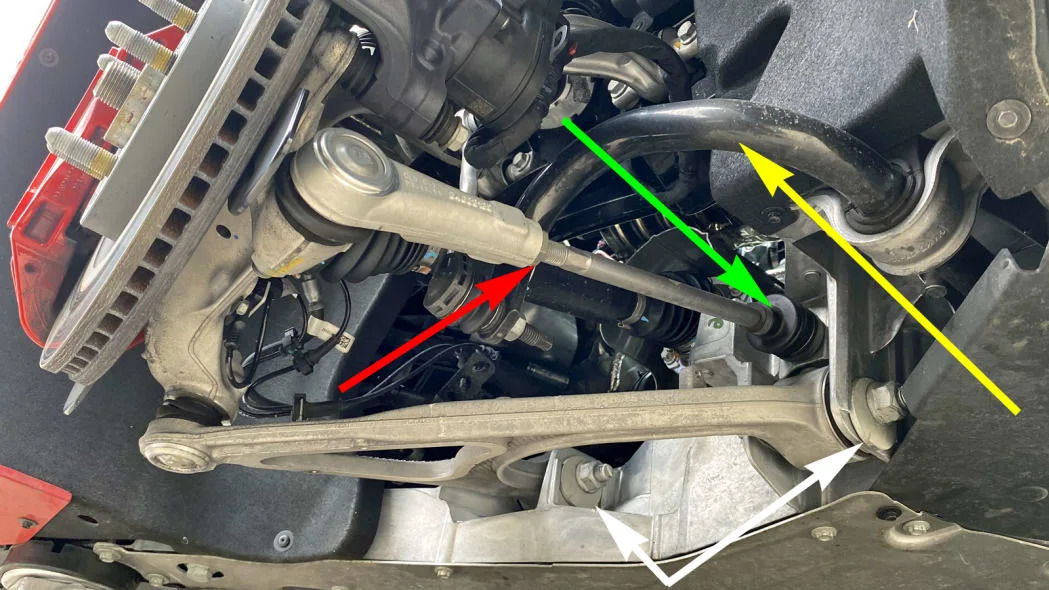

It’s also obvious that a switch to coil springs (yellow) has been made back here, too. And the manually-adjustable spring perches (green) that come with the Z51 package are, in fact, present back here because there’s no point in fitting a hydraulic suspension lift at the rear. Interestingly, the adjustable perch has a protective collar (red) that extends down to cover the shock body’s external threads so they don’t get damaged – a nice touch.

Like we saw in the Acura NSX, the lower end of the rear damper attaches high on the rear knuckle (yellow) at a point that’s above the massive drive axle (green).

There’s room to do this on the C8 because mid-engine styling usually comes with high rear haunches. Here the upper ends of the shock towers are quite a bit higher than the engine itself, in fact. And just like we saw in the front, the control wire (yellow) for the MagneRide rear dampers comes straight out the top.

The lower shock mount bolt serves double duty because it’s also the attachment point for the rear stabilizer bar link (yellow). You know what this means, right? There’s no need for my usual motion ratio diagram. The coil-over spring and the stabilizer bar all connect directly to the knuckle itself for a 1-to-1 motion ratio. The spring and shock will get a minor deduction for the coil-over’s lean angle, but there’s no denying this is a tidy setup.

This view from below confirms the presence of a second wishbone (yellow), but there’s something odd about it.

The arm’s distinct A-shape is highly italicized to the point where its outer ball joint is comically far forward. And this is where the alphabet lets us down, because a GM engineer I spoke to called this an L-arm lower wishbone.

In this layout about half of the cornering loads (yellow) come straight in from the ball joint to the forward (left) bushing. But that lower ball joint is about as far ahead of the rear axle (and tire contact patch) as the toe-link is behind it, so the other half of the cornering load comes in through the toe-link itself, which means it isn’t JUST a toe link.

Why refer to this lower wishbone as an L-arm? Because the wishbone’s rear bushing is mainly there to brace the fore-aft position of the suspension and absorb the longitudinal component (green) of road impacts. The front and rear bushing have entirely different jobs, just like we saw in the front. In the minds of some, A-arms are symmetrical and have bushings that more-or-less functionally mirror one another. That’s not going on here.

The rear stabilizer bar (yellow) loops up and over all of this to join up with the link we saw earlier. And here you can see how the more-than-a-toe-link screws directly (green) into the rear subframe as in the McLaren GT. There’s also a jamb nut (red) near its midpoint where you can, in fact, make toe adjustments. Camber is easy to set using a pair of eccentrics (white) on the lower wishbone.

The rear brakes are based around another four-piston Brembo caliper with an open pad-extraction window. There’s no bridge bolt this time, and the pad retention pins are the familiar dual skewers (yellow) we normally see. I probably don’t need to tell you that the tiny caliper on the right is an electronically-actuated parking brake.

This Z51 Stingray is fitted with Michelin Pilot Cup Sport 4S tires. The 245/35ZR19 tires at the front are mounted on 19-by-8.5-inch wheels, and the assemblies weigh 53.5 pounds. In back you’ll find 305/30ZR20 tires on 20-by-11-inch wheels, and that combination weighs in at 66.5 pounds. That’s not as light as what we saw on the McLaren GT recently, but that car costs three times as much as the C8 Corvette.

And that’s just the thing. Throughout, I had to keep reminding myself that this car starts at just under $60,000. The red example we looked at here stickered at about $85,000 or so because it’s an optioned up 3LT with the Z51 package, MagneRide dampers, the nose lift and several other upgrades, but that's still a bargain based on the kind of hidden engineering we just stared at. Those who spent years arguing that a mid-engine Corvette would bankrupt their loyal customers need to come up with another argument.

Contributing writer Dan Edmunds is a veteran automotive engineer and journalist. He worked as a vehicle development engineer for Toyota and Hyundai with an emphasis on chassis tuning, and was the director of vehicle testing at Edmunds.com (no relation) for 14 years.

You can find all of his Suspension Deep Dives here on Autoblog.

Related Video:

Sign in to post

Please sign in to leave a comment.

Continue