Every year, enough teenagers to fill three large high schools die in car accidents in the U.S.

If you accumulated all their photos, it would make the saddest of yearbooks: Faces of seniors with unfulfilled plans for college, pictures of juniors who never made it to the SAT. Sophomores who'd never been to the prom. Freshmen who'd never been kissed.

And yet every day, parents in many states get in line at their local Department of Motor Vehicles on their children's 16th birthday to help their kids get access to one of the most dangerous activities they will ever do. The same parents who wrapped their coffee table corners in foam when their children were learning to walk, who insisted their children wear helmets to ride a tricycle, and who would never dream of letting their 16-year-old parachute out of a plane, hand over the keys to the car and, fingers crossed, pray their children will come home.

While society spends an enormous amount of time and money talking about the dangers of drugs and alcohol, much fewer resources are spent on teaching teens about the thing that is most likely to kill them: Car accidents.

Video games to cars

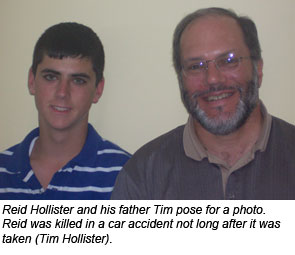

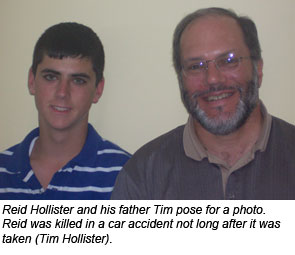

"The car culture in this country is a huge problem," says Tim Hollister, a teen safety advocate in Connecticut. Cars and unsafe driving habits are ingrained into the culture, through video games, music, and even children's movies.

And parents, he says, are largely blind to the problem. Our culture treats the process of getting a license as a right of passage, when it should be more akin to getting a pilot's license. Indeed, many parents are relived when their sixteen and seventeen year-olds get licenses, cutting down on the amount of chauffeuring they have to do to school and friends' houses.

"Properly supervising a teen driver in this country forces you to swim against the tide and put popular culture out of your mind," he says.

Hollister doesn't believe there is any such thing as a safe teen driver. And he's got research and personal experience backing him up. Researchers have found that teen drivers don't think about risk the same way as adults, so they take bigger chances behind the wheel. And their inexperience when things go wrong compounds the problem, often ending with disastrous results.

The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia and State Farm Insurance found that 75% of fatal accidents caused by teens were caused by one of three mistakes from the teen driver: driving too fast relative to road conditions or weather; not scanning the road well enough, identifying what was coming ahead or from the side; or distracted by something inside or outside the vehicle.

Graduated licenses are one way states are attempting to cut back on fatalities. Adopted by almost every state in the U.S., graduated licenses put caps on the hours teens can drive, how many other passengers they can have in a car, and insist they do 30 to 50 hours of practice before moving on to an unrestricted license.

But graduated licenses can only go so far. CHOP also found that parental involvement – involvement that is far more strict than many parents may feel comfortable with – helps some mistakes from happening.

Even 'safe' drivers at risk

Hollister taught his son, Reid, to drive. Reid, 16 when he earned his license in Connecticut, was a cautious driver; very alert, and motivated to learn. He took classes through a local private driving school, and mastered everything his father asked. He got one ticket, for failing to signal before changing lanes, and then another for going 5 mph over the speed limit. Neither incident alarmed his father.

Nothing else stands out as a red flag, Hollister says, when he thinks back on how his son learned to drive and what happened in the 11 months when Reid had his license.

"Looking back, I don't think I understood anywhere near how dangerous it was," Hollister says. "The idea that he could go into an uncontrolled skid and lose his life never crossed my mind."

On Dec. 2, 2006, Reid was traveling down an unfamiliar highway with two high school freshmen girls in a 1999 Volvo S80, The roads were wet after a short rain storm passed through.

It was around 9:30 p.m. when Reid entered a turn going about 65 mph near exit 34 on I-84 in Plainville, Conn. His speed was too fast for the turn, and the car began to skid. Reid panicked, and turned the wheel in the same direction the car was going, which did nothing to slow the vehicle down.

The car spun several times. In a stroke of what appears to be incredibly bad luck – but may actually be a result of driver inexperience, the teenagers hit the end of the guardrail. The guard rail punctured the car at the driver side, and killed Reid. The two passengers survived.

Months later, as a way to process his grief, Hollister started a blog about teen driving safety.

"I got into this not because I made an obvious mistake, but because I didn't and my son still had a fatal crash," he says. "He was an alert, coordinated driver. There was no alcohol or drugs. He wasn't on his cellphone."

What happened to Reid could happen to any young driver:

"He simply made a classic inexperienced driver's mistake," Hollister says.

The mistakes they make

When adults talk to teens about driving, they tend to talk about being responsible. Don't text, they say. Don't drink. Wear your seatbelt. Be responsible. Most adults take the act of driving so much for granted after so many years of doing it that they have forgotten what it was like to first drive at 15, 16 or 17. (The legal driving ages in several states is 15, including Idaho, Hawaii, Louisiana, Michigan, Montana and New Mexico, South Carolina and Wyoming. The legal driving age in South Dakota is 14.)

Sometimes parents or schools screen horrific videos, showing the aftermath of horrible crashes or YouTube public service announcements about the horrors of texting and driving.

It's a bit of a guilt trip, honestly, and it may not be very effective. It's like trying to get children to be better swimmers by lecturing them on how to avoid drowning.

We know enough about how teens drive, and more importantly, the mistakes they make, to zero in on the skills they lack and hopefully give educators the ammunition to fix those problems.

AOL Autos has been monitoring news reports of teen accidents for more than a year. After reading the stories, certain patterns emerge:

Speeding: Every day, newspapers and local TV stationsreport stories about teens dying in crashes caused by speeding. Or worse, the speeding causes the death of passengers or people in other cars.

It's speeding, not texting or driving drunk, that causes the most one-car fatal accidents. Accidents where a teen is simply driving down a road, too fast, and misjudges a curve or a bump in the road. Worst of all perhaps, they are seldom in the car alone.

It was speed that killed three teens in Ohio over Fourth of July weekend this year. The sun was shining, and the road was dry. Two 19-year-old men and an 18-year-old man were in the car, which witnesses estimate was going 70 mph in a 35 mph zone. The driver, Cody Mazuk, tried to pass another car.

His vehicle struck a rock, then a tree, and then a second rock before going airborne and slamming into a second tree. Mazuk and Jeremiah Fischer, 18, died at the scene. Christopher Drummond, 19, died a day later.

In a sad bit of irony, the same scenario played out the same weekend in Pennsylvania. Except this time, there were four teens in the car. The driver, 16-year-old Colin McElroy, was going 75 mph in a 35 mph zone. McElroy lost control, hit a tree which sheared off the roof, and caused the car to flip. All four teens died.

Those accidents were just a taste of the thousands annually that cause teen deaths – AllState Insurance estimates that 40% of the 5,000 to 6,000 teens deaths each year are caused by speeding.

The Center for Disease Control says teens are more likely to speed than older drivers, and they don't allow for enough space between themselves and cars around them.

Didn't see it coming: In too many cases, teen drivers get into accidents because they don't look out for dangers well enough. Maybe it's because driving is new to them, and they're already mentally juggling too much, or maybe they just don't have enough experience to know what to look out for.

But since they aren't looking out for danger, when it comes their way, they often overreact and turn a bad situation into a deadly one.

In July, 17-year-old Ryan Fant from Townville, S.C., died after he swerved to avoid a deer. Police say he was driving in his 1994 Ford pickup truck when the deer dashed into the road. Ryan over-corrected to the right, and the truck flipped.

Ryan was ejected from the truck and died. Two passengers inside the car were unharmed.

Some professional driving instructors advise that drivers shouldn't swerve when animals enter the road. They should brake hard, and keep in their lane. The dangers of swerving to avoid the animal too often result in dangerous accidents.

Inexperienced drivers often swerve dramatically when something unexpected happens on the road.

In July, 17-year-old Zechariah Cicalo was driving in an accident that killed himself, his mother and his sister. Witnesses said Zechariah was speeding down the road in Kokomo, Ind., when he drove a little off the road and hit a guardrail. He over-corrected, and the car flipped and landed in a drainage ditch.

They were all wearing seatbelts.

Lightpoles, trees and dividers: In the panic of losing control, teens (and older drivers, for sure) often look exactly where they shouldn't: At the obstacle they should be trying to avoid.

When learning to ski through trees or mountain bike in the woods, participants are taught to look at the spaces between the trees. Don't focus on the trees, because that's where you will go, they're taught.

That's why the rate of fatal one-car accidents is much higher for teens that for older drivers, according to the Insurance Institute of Highway Safety (IIHS). The number of fatal single-vehicle accidents involving teens is startling: A full 50% of fatal teen accidents in recent years have been one-car accidents, according to the IIHS.

At Ford's Driving Skills for Life, the instructors spend about 20 minutes teaching teens how to control a car that's skidding, and where to look during the skid.

"When we look at accidents where there was a car skidding for 300 feet and then hitting a one-and-a-half foot telephone pole, I think 'That's amazing car control,'" says Mike Speck, one of the instructors at Ford's program. "Wherever you look, your hands and feet will go exactly in that direction."

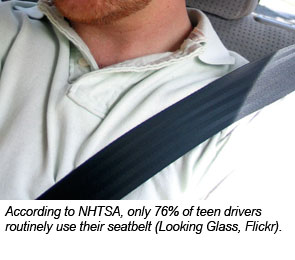

Not wearing seatbelts: Seatbelt use is a battle safety advocates have been fighting for decades. Increased seatbelt use is credited as one of the biggest reasons overall traffic fatalities fell to an all-time low in 2010 of 32,000 deaths.

Still, teens buckle up far less often than adults, according to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA). Only 76% of teens regularly use their seatbelt. And more alarming are the fatality statistics: A full 58% of teens who died in car accidents in 2006, the last year numbers are available, weren't wearing their seatbelts.

In August, 18-year-old Hippolito Hernandez killed himself and put his girlfriend in critical condition when he crashed into a tree in Pine Forest, Calif. Neither were wearing seatbelts.

Alcohol: Oddly, drinking and driving is not something teens do more than the rest of the population. That's unusual for two reasons: First, teens don't process risk as well as older people, so one would expect them to have a greater incidence of DUIs.

On the other hand, the drinking age in all U.S. states is 21. So the number should in fact be much smaller.

But 31% of teens in fatal accidents had .01 blood alcohol content (BAC); for adults that figure is 37%. About 26% of teens had a BAC of .08 or greater, NHTSA says; for adults that figure is 32%.

Alcohol use in teens exacerbates some of their risk-taking habits. Teens who have been drinking often don't wear seatbelts: Of those who were drinking and driving and ended up dying in a car crash, 75% were not wearing seatbelts.

Next week

AOL's series on teen driving continues next week, with a look at the efficacy driver's education programs and state laws that could help reduce the fatality rates.

If you accumulated all their photos, it would make the saddest of yearbooks: Faces of seniors with unfulfilled plans for college, pictures of juniors who never made it to the SAT. Sophomores who'd never been to the prom. Freshmen who'd never been kissed.

And yet every day, parents in many states get in line at their local Department of Motor Vehicles on their children's 16th birthday to help their kids get access to one of the most dangerous activities they will ever do. The same parents who wrapped their coffee table corners in foam when their children were learning to walk, who insisted their children wear helmets to ride a tricycle, and who would never dream of letting their 16-year-old parachute out of a plane, hand over the keys to the car and, fingers crossed, pray their children will come home.

While society spends an enormous amount of time and money talking about the dangers of drugs and alcohol, much fewer resources are spent on teaching teens about the thing that is most likely to kill them: Car accidents.

Video games to cars

"The car culture in this country is a huge problem," says Tim Hollister, a teen safety advocate in Connecticut. Cars and unsafe driving habits are ingrained into the culture, through video games, music, and even children's movies.

And parents, he says, are largely blind to the problem. Our culture treats the process of getting a license as a right of passage, when it should be more akin to getting a pilot's license. Indeed, many parents are relived when their sixteen and seventeen year-olds get licenses, cutting down on the amount of chauffeuring they have to do to school and friends' houses.

"Properly supervising a teen driver in this country forces you to swim against the tide and put popular culture out of your mind," he says.

Hollister doesn't believe there is any such thing as a safe teen driver. And he's got research and personal experience backing him up. Researchers have found that teen drivers don't think about risk the same way as adults, so they take bigger chances behind the wheel. And their inexperience when things go wrong compounds the problem, often ending with disastrous results.

The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia and State Farm Insurance found that 75% of fatal accidents caused by teens were caused by one of three mistakes from the teen driver: driving too fast relative to road conditions or weather; not scanning the road well enough, identifying what was coming ahead or from the side; or distracted by something inside or outside the vehicle.

Graduated licenses are one way states are attempting to cut back on fatalities. Adopted by almost every state in the U.S., graduated licenses put caps on the hours teens can drive, how many other passengers they can have in a car, and insist they do 30 to 50 hours of practice before moving on to an unrestricted license.

But graduated licenses can only go so far. CHOP also found that parental involvement – involvement that is far more strict than many parents may feel comfortable with – helps some mistakes from happening.

Even 'safe' drivers at risk

Hollister taught his son, Reid, to drive. Reid, 16 when he earned his license in Connecticut, was a cautious driver; very alert, and motivated to learn. He took classes through a local private driving school, and mastered everything his father asked. He got one ticket, for failing to signal before changing lanes, and then another for going 5 mph over the speed limit. Neither incident alarmed his father.

Nothing else stands out as a red flag, Hollister says, when he thinks back on how his son learned to drive and what happened in the 11 months when Reid had his license.

"Looking back, I don't think I understood anywhere near how dangerous it was," Hollister says. "The idea that he could go into an uncontrolled skid and lose his life never crossed my mind."

On Dec. 2, 2006, Reid was traveling down an unfamiliar highway with two high school freshmen girls in a 1999 Volvo S80, The roads were wet after a short rain storm passed through.

It was around 9:30 p.m. when Reid entered a turn going about 65 mph near exit 34 on I-84 in Plainville, Conn. His speed was too fast for the turn, and the car began to skid. Reid panicked, and turned the wheel in the same direction the car was going, which did nothing to slow the vehicle down.

The car spun several times. In a stroke of what appears to be incredibly bad luck – but may actually be a result of driver inexperience, the teenagers hit the end of the guardrail. The guard rail punctured the car at the driver side, and killed Reid. The two passengers survived.

Months later, as a way to process his grief, Hollister started a blog about teen driving safety.

"I got into this not because I made an obvious mistake, but because I didn't and my son still had a fatal crash," he says. "He was an alert, coordinated driver. There was no alcohol or drugs. He wasn't on his cellphone."

What happened to Reid could happen to any young driver:

"He simply made a classic inexperienced driver's mistake," Hollister says.

The mistakes they make

When adults talk to teens about driving, they tend to talk about being responsible. Don't text, they say. Don't drink. Wear your seatbelt. Be responsible. Most adults take the act of driving so much for granted after so many years of doing it that they have forgotten what it was like to first drive at 15, 16 or 17. (The legal driving ages in several states is 15, including Idaho, Hawaii, Louisiana, Michigan, Montana and New Mexico, South Carolina and Wyoming. The legal driving age in South Dakota is 14.)

Sometimes parents or schools screen horrific videos, showing the aftermath of horrible crashes or YouTube public service announcements about the horrors of texting and driving.

It's a bit of a guilt trip, honestly, and it may not be very effective. It's like trying to get children to be better swimmers by lecturing them on how to avoid drowning.

We know enough about how teens drive, and more importantly, the mistakes they make, to zero in on the skills they lack and hopefully give educators the ammunition to fix those problems.

AOL Autos has been monitoring news reports of teen accidents for more than a year. After reading the stories, certain patterns emerge:

Speeding: Every day, newspapers and local TV stationsreport stories about teens dying in crashes caused by speeding. Or worse, the speeding causes the death of passengers or people in other cars.

It's speeding, not texting or driving drunk, that causes the most one-car fatal accidents. Accidents where a teen is simply driving down a road, too fast, and misjudges a curve or a bump in the road. Worst of all perhaps, they are seldom in the car alone.

It was speed that killed three teens in Ohio over Fourth of July weekend this year. The sun was shining, and the road was dry. Two 19-year-old men and an 18-year-old man were in the car, which witnesses estimate was going 70 mph in a 35 mph zone. The driver, Cody Mazuk, tried to pass another car.

His vehicle struck a rock, then a tree, and then a second rock before going airborne and slamming into a second tree. Mazuk and Jeremiah Fischer, 18, died at the scene. Christopher Drummond, 19, died a day later.

In a sad bit of irony, the same scenario played out the same weekend in Pennsylvania. Except this time, there were four teens in the car. The driver, 16-year-old Colin McElroy, was going 75 mph in a 35 mph zone. McElroy lost control, hit a tree which sheared off the roof, and caused the car to flip. All four teens died.

Those accidents were just a taste of the thousands annually that cause teen deaths – AllState Insurance estimates that 40% of the 5,000 to 6,000 teens deaths each year are caused by speeding.

The Center for Disease Control says teens are more likely to speed than older drivers, and they don't allow for enough space between themselves and cars around them.

Didn't see it coming: In too many cases, teen drivers get into accidents because they don't look out for dangers well enough. Maybe it's because driving is new to them, and they're already mentally juggling too much, or maybe they just don't have enough experience to know what to look out for.

But since they aren't looking out for danger, when it comes their way, they often overreact and turn a bad situation into a deadly one.

In July, 17-year-old Ryan Fant from Townville, S.C., died after he swerved to avoid a deer. Police say he was driving in his 1994 Ford pickup truck when the deer dashed into the road. Ryan over-corrected to the right, and the truck flipped.

Ryan was ejected from the truck and died. Two passengers inside the car were unharmed.

Some professional driving instructors advise that drivers shouldn't swerve when animals enter the road. They should brake hard, and keep in their lane. The dangers of swerving to avoid the animal too often result in dangerous accidents.

Inexperienced drivers often swerve dramatically when something unexpected happens on the road.

In July, 17-year-old Zechariah Cicalo was driving in an accident that killed himself, his mother and his sister. Witnesses said Zechariah was speeding down the road in Kokomo, Ind., when he drove a little off the road and hit a guardrail. He over-corrected, and the car flipped and landed in a drainage ditch.

They were all wearing seatbelts.

Lightpoles, trees and dividers: In the panic of losing control, teens (and older drivers, for sure) often look exactly where they shouldn't: At the obstacle they should be trying to avoid.

When learning to ski through trees or mountain bike in the woods, participants are taught to look at the spaces between the trees. Don't focus on the trees, because that's where you will go, they're taught.

That's why the rate of fatal one-car accidents is much higher for teens that for older drivers, according to the Insurance Institute of Highway Safety (IIHS). The number of fatal single-vehicle accidents involving teens is startling: A full 50% of fatal teen accidents in recent years have been one-car accidents, according to the IIHS.

At Ford's Driving Skills for Life, the instructors spend about 20 minutes teaching teens how to control a car that's skidding, and where to look during the skid.

"When we look at accidents where there was a car skidding for 300 feet and then hitting a one-and-a-half foot telephone pole, I think 'That's amazing car control,'" says Mike Speck, one of the instructors at Ford's program. "Wherever you look, your hands and feet will go exactly in that direction."

Not wearing seatbelts: Seatbelt use is a battle safety advocates have been fighting for decades. Increased seatbelt use is credited as one of the biggest reasons overall traffic fatalities fell to an all-time low in 2010 of 32,000 deaths.

Still, teens buckle up far less often than adults, according to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA). Only 76% of teens regularly use their seatbelt. And more alarming are the fatality statistics: A full 58% of teens who died in car accidents in 2006, the last year numbers are available, weren't wearing their seatbelts.

In August, 18-year-old Hippolito Hernandez killed himself and put his girlfriend in critical condition when he crashed into a tree in Pine Forest, Calif. Neither were wearing seatbelts.

Alcohol: Oddly, drinking and driving is not something teens do more than the rest of the population. That's unusual for two reasons: First, teens don't process risk as well as older people, so one would expect them to have a greater incidence of DUIs.

On the other hand, the drinking age in all U.S. states is 21. So the number should in fact be much smaller.

But 31% of teens in fatal accidents had .01 blood alcohol content (BAC); for adults that figure is 37%. About 26% of teens had a BAC of .08 or greater, NHTSA says; for adults that figure is 32%.

Alcohol use in teens exacerbates some of their risk-taking habits. Teens who have been drinking often don't wear seatbelts: Of those who were drinking and driving and ended up dying in a car crash, 75% were not wearing seatbelts.

Next week

AOL's series on teen driving continues next week, with a look at the efficacy driver's education programs and state laws that could help reduce the fatality rates.

Sign in to post

Please sign in to leave a comment.

Continue